Improving Open Adoptions

Adoption Advocate No. 174 - This article covers what openness means in the context of adoption and how adoptive parents can, through openness, help adoptees integrate and heal. Lori Holden, adoptive parent, author, speaker, and podcaster, proposes three shifts adoptive parents can make—to better focus on what really matters, answering the question of how adoptive parents can create and support healing and integration for adoptees in the ways they “do” adoption in their homes and within the larger culture?

Three Shifts to Bridge the Gap Between Birth Families and Adoptive Families for the Adoptees We Love

Adoption creates a split between a person’s biology and biography, and openness is an essential way to help adoptees heal this split. [1]

This article covers what openness means in the context of adoption and how adoptive parents can, through openness, help adoptees integrate and heal. There are three shifts adoptive parents can make—supported by adoption professionals—to better focus on what really matters. This article addresses situations faced by adoptive parents who have contact with birth parents, those who do not and feel that is just as well, and, finally, those who wish to be in contact with birth parents but, for various reasons, are not.

So, let’s explore this question: How can we create and support healing and integration for adoptees in the ways we “do” adoption in our homes and within our culture?

The Benefits of Openness

The Inclusive Family Support Model, [2] a framework for understanding and supporting relationships between birth families and adoptive families, identifies significant benefits of openness in adoption: [3]

- Openness strengthens an adoptee’s sense of identity.

- Openness encourages an adoptee’s attachment to adoptive parent(s).

- Openness can decrease an adoptee’s sense of abandonment.

How can these statements be true when they seem counterintuitive? After all, many think that having birth parents around is confusing to an adoptee. Many believe that the presence of birth parents, whether physical or psychological, dilutes attachment to adoptive parents. Some despair that a deep and unhealable wound exists for adoptees due to maternal separation.

But evidence tells us the opposite about confusion, dilution, and brokenness. Let’s look more closely at this magic ingredient, openness.

In one sense, openness refers to the willingness and ability of adoptive parents to enter into conversations about adoption—both the easy ones (Did I grow in your belly, Mama? Why do we have different color hair, Daddy?) and the harder ones (Mom, I’m thinking about my birth mom a lot. Can I go live with her now? Dad, I worry I was conceived through sexual assault. Was I?).

Perhaps you fear these hard questions, these difficult conversations. No wonder— they’re scary! But as adoptive parents, we need to be able to enter these spaces with our adoptees. We don’t always need to know the right words to say, but it does help to cultivate an orientation from which to formulate our responses. We need support in knowing how to navigate these conversations, the kind of support that can infuse us with courage and confidence when intimidating discussions must be had.

The truth is, questions like these tend to arise only in homes where an adoptee feels like it’s safe to bring up hard topics with their parents. Otherwise, these sentiments go unspoken and the adoptee is left to navigate their wonderings and their complicated emotions without the help of their most trusted guides—their parents. If an adoptee does gather the courage to ask sensitive questions, but then senses our reluctance to “go there” with them, the adoptee may not offer such an invitation again soon. [4]

Learn More

Check out the Inclusive Family Support Model webinar with Lori Holden and Kara Andersen, available in NCFA’s online learning library.

Characteristics of Openness

Body, Thoughts, Beliefs

Openness means not closed. There’s a stance that goes with closedness: a tension in the belly, chest, and throat, with arms folded, perhaps in protection or possibly signaling a “no” to external input.

And there’s a stance that goes with openness: belly, chest, and throat relaxed, arms and palms loose, signaling a willingness to allow information and people in, and to engage.

There are thoughts in adoption that go with closedness, such as I can’t believe the birth mom stood us up again. We’re done trying!

And there are thoughts that go with openness, such as I wonder why she might be unable to show up reliably for visits? Our thoughts come from our histories and experiences, and the reasons why we might tend toward closedness or openness may not be consciously known, even to ourselves.

Beneath our thoughts are our beliefs, even less accessible to our conscious minds. Beliefs that reside under closedness may be something like If my son is thinking about his birth mom, that means I’m not enough for him, or It really hurts to see him with his birth dad because they’re so alike in ways I’m not.

And there are beliefs that underlie openness—perhaps less deeply buried due to a parent’s willingness to perform ongoing inner excavation—such as The stronger the connection my child has with his birth parents, the stronger his connections are within himself and with us.

Curiosity and Humility

A companion to openness is curiosity. Curiosity keeps us in a growth mindset rather than in a fixed mindset. If a birth parent is struggling with substance use disorder, for example, a lack of curiosity can send us directly to judgment, whereas the exercise of curiosity makes us more likely to wonder about the context surrounding addiction and offer compassion. A key phrase to summon curiosity when in a vexing situation is “I wonder.” I wonder what she has been through to make the decisions she makes. Therapist Robyn Gobbel says “all baffling behavior makes sense” [5] when our curiosity leads us to explore the context it arises from. (This goes for our children’s baffling behavior, too!)

Curiosity leads to humility, another component of being open. When we’re humble, we accept that we don’t know everything. How could we? Humility can help moderate the imbalance in the power dynamic between adoptive and birth parents. Adoptive mom and children’s book author Leah Campbell spoke of this power imbalance on my podcast, Adoption: The Long View. “I have more power than my daughter. I have more power than her mom. It’s my responsibility to give power where I can.” [6]

The words “humility” and “humble” come from a Greek root that means “grounded.” When we are grounded, we don’t see ourselves as better than or less than our child’s birth parents. Valuing birth parents, whether they’re present or not, serves our child in two ways. The first is in their identity formation and integration. Wouldn’t you find it easier to know you come from people about whom your parents speak respectfully rather than in a derogatory way? The second is that when we value both sides of the partnership of creating and raising our precious children—differing roles but each integral to our child—we decrease the chances that the child will experience split loyalties. Splitting loyalties is the opposite of integration and healing, [7] and can be quite painful for an adoptee. [8]

When parents relate with their child and with birth parents in a grounded way, they send the subtle yet important message that they are secure in these relationships and secure enough to handle questions or concerns from their child. Parents for whom openness comes naturally tend to interact from a place of abundance rather than scarcity.

This is the first shift to help bridge the gap for adoptees: the shift from closedness to openness. When we become more mindful of our stance, our thoughts, our beliefs, and the power we hold, we can choose openness over closedness. (This does not mean no boundaries, though—boundaries will be discussed!)

Openness Allows for BothAnd [9]

The old way of doing adoption was an Either/Or construct. Adoptees often had access to only one set of their parental puzzle pieces unless they set out on the arduous task of searching and reuniting with birth parents. Many adult adoptees report that their adoptive parents were unable to tolerate their search for birth family and they were consequently faced with a no-win decision to alienate their parents, search in secret, deny their desire to search, or wait until their parents die (sometimes not even then, so deep is the wound of split loyalties).

Things may not be that dire in these days of open adoption, when birth parent identity is often known and contact has sometimes been established. But an Either/Or feeling in adoptive parents remains. Adoptees can feel when we are uncomfortable talking about their birth parents.

Even with decades of open adoption practices behind us, this Either/Or sentiment continues to reverberate not just in our homes but also in our culture. Adoptive parents may never use the word “real” regarding parentage, but our adoptees may still come home from elementary school saying Aidan asked who my real mom is. Either/Or in adoption remains part of our social fabric, bolstered by media and social media stories that stereotype adoptive families, birth families, and adoptees as two dimensional. You can have either these parents OR those parents, our culture tells adoptees, but only one set of parents can be real. The adoptee is left to think: So, what does that make me?

Adoptee Math

Openness shifts us into BothAnd. The more open and expansive adoptive parents can be, the freer adoptees are to claim and be claimed by all their important people. Many in our society have been acculturated to Either/Or, which is why, when an adoptee says they are thinking about their birth mom, it can feel like a subtraction to adoptive parents. The math of the closed adoption era was subtraction (of birth parents), substitution (of adoptive parents), and division (of the adoptee’s mind, heart, loyalty). The math that better serves an adoptee’s efforts to integrate are addition (biology + biography) and multiplication (of love, and also of complexity).

Pro tip

If and when you find yourself subconsciously going into subtraction or substitution, simply notice it, then consider choosing addition instead. See openness benefit number two in the previous section.

When adoptive parents begin to see that their underlying beliefs are rooted in closedness and the Either/Or construct, they become open—eager, even—to examining those beliefs anew.

If my son is thinking about his birth mom, does that necessarily mean he’s devaluing me? Perhaps not! Perhaps he can love us both—and it’s not a contest anyway. In fact, if I inwardly grant him my permission to think about her and love her, that will likely strengthen the bond I share with him rather than weaken it.

Looking under our own hood at times when we start to feel tight and closed takes courage and commitment. Consider this: Who among us wouldn’t run into the path of a bus to protect our child? Surely, then, we can summon such courage and commitment to excavate some of our own auto-pilot thoughts and beliefs that may end up causing our child pain.

This is the second shift to help bridge the gap for adoptees: from Either/Or to BothAnd.

Open Adoption ≠ Openness in Adoption

Contact ✅ Openness ⛔

Open adoption and openness in adoption are related but not synonymous. Adoptive parents who are able to provide contact with birth parents may still seem unapproachable about some things to their child, less than willing to enter into conversations with at least a base level of comfort. And it’s important to note that this is something parents cannot fake. If we are not comfortable, our child will know and respond accordingly. The only way to appear comfortable is to actually be comfortable, which can happen when we commit to a path of self-inquiry.

Two, of many, accessible ways to start this process are:

Begin to carve out quiet time to journal regularly, to find calm moments to delve into your thoughts and feelings and bring them up from below the surface. It is the metacognition of thinking about our thinking that allows us to tend to old wounds that hold us back from more fully engaging with our child and with our child’s birth family.

Find an attachment therapist who can help you discover the places within you that need tending in order for you to better attend to the places within your child that need tending. This is adult work and it should never be the child’s role to make the parent feel whole.

Contact ⛔ Openness ✅

Likewise, there are many reasons why adoptive parents, even when open to it, would not be able to provide contact with birth family: birth parents are unknown, on another continent, incarcerated, deceased, unsafe, otherwise unavailable, or have opted out. Contact may be out of the control for the adoptive parents to manifest. But even with limitations such as these, adoptive parents can still cultivate a sense of openness that their child feels and benefits from. How can this be? It’s because…

Openness ≠ Contact

Contact is an imperfect measure of an open adoption for two reasons. It is imprecise, because there is no consensus whether we are measuring the type of contact, the frequency of contact, the quality of contact, or something else. In addition, it is exclusive. Contact as a measure excludes many families formed through international adoption, in which contact may not be possible, and some formed through adoption from foster care, in which contact may be unwise.

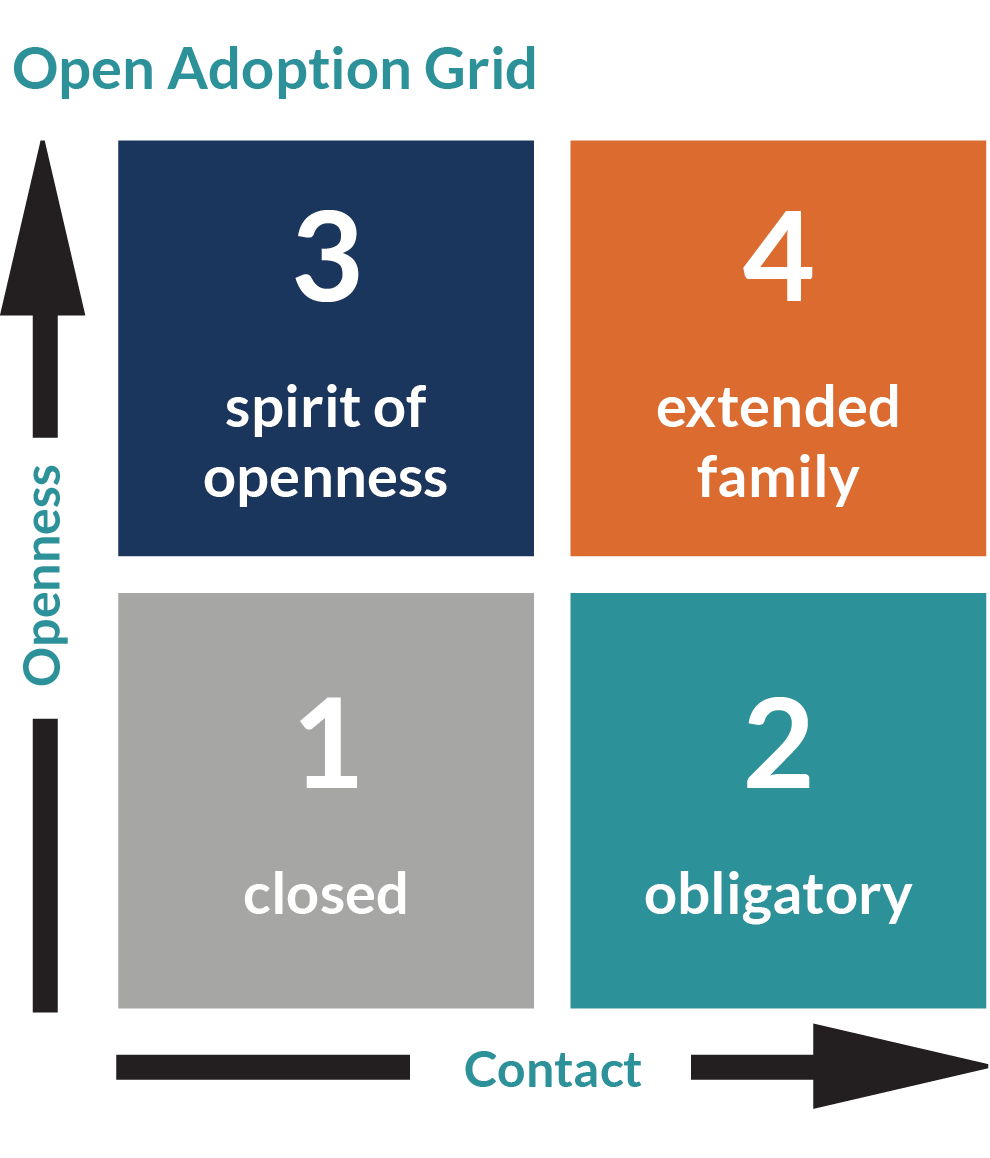

Since the earliest days of “open adoption,” we have used contact as the measure. Consider instead the Open Adoption Grid. [10]

Open Adoption Grid

In Quadrant 1 (gray) there is little to no birth family contact, and conversations about adoption are not easily had. This is what many adoptions felt like during the closed adoption era, when parties were hopeful that everyone would “just move on” and many felt that conversations about adoption were not needed. But now we know better.

In Quadrant 2 (teal) there is contact with birth family but not much openness around dealing with the complexities that contact brings. This is where contact feels like a duty, like checking the boxes to meet a commitment to birth parents. It is missing a sense of relationship and an ability to talk about adoption-related issues as they arise through the child’s developmental stages.

Families in Quadrant 3 (blue) may not have contact with birth parents for all the reasons mentioned regarding availability and safety. But even without contact, parents here feel open to their child and willing to enter into hard conversations. They intentionally carve out space for the existence of birth parents—even in their absence—through pictures, conversations, memories, and wondering about birth parents alongside the adoptee.

In Quadrant 4 (orange) birth family members are present and safe. In this quadrant, adoptive parents are open to dealing with the complexities of adoption and having conversations as they arise over the years and through the adoptee’s developmental stages (as well as the parents’!).

This is not a sequential model, and not all families will be able to reside in Quadrant 4. What matters in bridging the gap between adoptive and birth parents, according to adoptees, [11] is elevation on the grid. In other words, the more that adoptive parents can “go there” with adoptees, the better parents can support adoptees in integrating their identity. Aim for Quadrants 3 and 4.

When parents orient on openness first, contact follows. Rather than fearing contact, parents actually desire as much contact as they can safely get, and they seek creative ways to make contact happen. When parents begin doing the work of getting out of their own way, they also get out of their child’s way. The agency professionals I’ve presented to immediately grasp the usefulness of helping their clients orient first on openness, which feels less distressing to them than contact.

Which brings us to boundaries.

Pro tip

To discover where you land on the Inclusive Family Support Model, [12] which is based on the Open Adoption Grid, take a self-assessment at https://bit.ly/AmaraOpennessAssessment

Openness and Boundaries

Does an emphasis on openness mean adoptive parents need to leave ourselves wide open to just about anything? That we give up our sovereignty or that we co-parent with birth parents?

Quite the contrary. The very health and structure of our relationships with birth family members relies on the quality of the boundaries we set and the way we set them.

We tend to think of boundaries as things that keep people away. But according to Prentiss Hemphill, “boundaries are the distance at which I can love you and me simultaneously.” [13] To reframe, boundaries don’t keep people apart; they are what allow people to come together.

Closed adoption gave us a wall. Open adoption installed a door in the wall. But doors have two settings: open and closed. Too many open adoptions close when things get tough, and the adoptee remains living in the Either/Or of a wall.

Openness in adoption gives that door a screen, a more flexible and responsive boundary than a door. Our job as adoptive parents is to continually set the mesh of the screen to let as much in as is beneficial for all involved under changing conditions.

Boundaries are the mesh—the screen door—in our adoptions. We do not set them and forget them; we are constantly reassessing to know when they can be loosened and when they need to be tightened. And we do so mindfully and with self-awareness of what we bring to the mesh-setting.

When our boundary is approached or even crossed, we spring into action: Not okay! the warning lights tell us. We want to act immediately to protect what is precious.

This brings us to the third shift that helps adoptive families bridge the gap for adoptees: shifting from reacting to responding.

The difference between a reaction and a response can be a mere moment, a mere breath, just enough time to insert choice, a chosen course of action. After all, a literal knee-jerk reaction when the doctor taps your knee with a rubber mallet comes without any thought at all—the brain isn’t even consulted. But when the boundary involves a birth parent or our child, we do want to engage our brain. We do want to have at least two or three options for how to proceed, and then we do want to choose something that is likely, overall, to have the optimal impact on all.

But as Dr. Brad Reedy says in his work with parents, “you can’t always win, but you can choose how to lose.” [14] Sometimes we find ourselves in unsolvable problems in which the best we can hope for is to find an acceptable way to lose, balancing the trade-offs between our child, their birth parents, and ourselves.

Dr. Reedy also points out that the more inner work we do around our boundary setting, the more capacity we have to expand and remain grounded—yet another way our ongoing work serves our counterparts in adoption well. [15]

Incorporating the Three Shifts

With all that as a very brief primer, here is an example of what can happen when we make these three shifts.

A family is in an open adoption and has contact with the child’s birth mom. However, she sometimes shows up high, like today.

A reaction, which often stems from a closed stance, comes with very little thought:

That’s the third time she’s done this. It’s not good for Micah to see her high. We’re done. Visits are on hold until she gets her act together.

The win we would all look for would be that she would break her addiction. Barring that, though, we may only be able to choose how to lose. So, let’s tease this out a little more.

With an open stance and a moment to check in and ponder, a response might look like any or all of this:

- Hmm… it would certainly be easier not to have to keep navigating visits.

- It is hard for Micah to see and it is hard for me to manage!

- Do I have any underlying beliefs about people with substance use disorder?

- Am I judging her harshly because of my own experiences with a person who was addicted?

- Is there a way for me to show more compassion for what has brought her to this place? After all, trauma begets trauma, and people often try to numb what they don’t want to feel in various ways. My way is ________ (shopping, eating, drinking, busyness, social media scrolling, sugar, etc.).

- Is zero tolerance necessary, or is there any leeway?

- What are some ways we might support her in showing up sober? Maybe a certain time of day is better, or maybe there’s a location that’s more soothing to her—I will ask her.

- I wonder if there is something about visits that is especially difficult. Maybe there is context we don’t know about. I wonder if she would talk with us about it to help solve the issue around visits.

- If we cannot make this work with her now, maybe someone else in her family can maintain a connection with Micah for the time being.

- We will also talk with Micah in an age appropriate way about what it is like to be addicted to something, how overpowering that can be. We may even get an adoption-competent therapist to help us so we do not bring a different kind of harm to him as we handle this series of conversations.

Curiosity opens up explorable ways to let in the benefits of birth family contact while also trying to keep out the problematic parts. This is the screen mesh. We need to make sure we don’t close the mesh for our own comfort, but for our child’s overall benefit.

When we focus on openness, we become willing to look at what we ourselves bring to the situation. We get curious. What am I feeling? Is it envy of her biological connection to Micah? Is it superiority because I am clearly a better parent/person than she is? Is it anger because she makes my life so hard? Is that— wait—is that grief that I did not get to conceive and give birth to him? Oh dear…I do not want to go there, but maybe I…could?

And from the process of finding these deeper layers, a way to deal with a situation often becomes clear. Parents begin to acknowledge and heal their own wounds, making way for more creativity, openness, and compassion with their child.

A Call for True Openness

Let’s revisit the benefits of openness and see what a powerful effect it can have for adoptees:

- Openness strengthens an adoptee’s sense of identity by creating the space to freely and openly discuss their adoptedness with their parents.

- Openness encourages attachment to adoptive parents. By offering the adoptee the opportunity to hold both families as part of their story, we show we are okay with the big emotions that adoption brings. When our child feels they can bring their entire range of emotions to us, we offer them a sense of felt safety, comfort, and connection.

- Openness can decrease an adoptee’s sense of abandonment. When we have the capacity to walk alongside the adoptee through their struggle, sadness, and grief, we can help them process their sense of abandonment in a space of connection.

When we cultivate openness, we infuse curiosity, humility, groundedness, self-awareness, clarity, and connection into our relationships. In this way we help bridge the gap between biology and biography that adoptees live in.

“The birth parents we struggle to show grace to today were likely the kids 20-30 years ago we would have considered it a joy to foster.”

—Jason Johnson [16]

References

-

Holden, L., & Hass, C. (2015). The open-hearted way to open adoption: Helping your child grow up whole. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, Inc.

-

Amara. (2021, March 19). What is the Inclusive Family Support Model? [Video]. YouTube. https://youtu.be/QGP-bCx4BuE

-

Kim, J., & Tucker, A. (2019). The Inclusive Family Support Model: Facilitating openness for post-adoptive families. Child & Family Social Work, 25(1). https://doi.org/10.1111/cfs.12675

-

Easterly, S., & Holden, L. (2020, February 16). “I want my real mom!”- Says Sara Easterly. Lavender Luz. https://lavenderluz.com/sara-easterly

-

Gobbel, R. (2023). Raising kids with big baffling behaviors: Brain-Body-Sensory strategies that really work. Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

-

Holden, L. (Host). (2020, August 7). Cultivating openness in your adoption [Audio podcast episode]. In Adoption: The Long View. https://www.adopting.com/adoption-podcasts/adoption-the-long-view/interview-with-leah-campbell

-

Riley, D. (2018). Beneath the mask: Adoption through the eyes of adolescents. Adoption Advocate. 124. https://adoptioncouncil.org/publications/adoption-advocate-no-124/

-

Easterly, S., Vander Vliet Ranyard, K., & Holden, L. (Hosts). (2022, May 17). Problematic behaviors of birth parents [Video podcast episode]. In Adoption Unfiltered. https://youtu.be/ENzs7fdEClM

-

Here, the author deliberately does not separate “BothAnd” with a slash in an effort to convey wholeness and integration.

-

Holden, L. (2013, January 12). Open Adoption Grid: Adding a dimension to the open adoption spectrum. Lavender Luz. https://lavenderluz.com/open-adoption-grid/

-

Tucker, A. (2023). “You should be grateful”: Stories of race, identity, and transracial adoption. Beacon Press.

-

Amara. (2021, March 19). What is the Inclusive Family Support Model? [Video]. YouTube. https://youtu.be/QGP-bCx4BuE

-

Hemphill, P. [@prentishemphill]. (2021, April 5). “A reminder. Boundaries are the distance at which I can love you and me simultaneously.” [Photograph]. Instagram. https://www.instagram.com/p/CNSzFO1A21C/

-

Evoke Therapy Programs & Reedy, B. (2023, June 8). Abandonment [Video]. YouTube. https://youtu.be/AwZSh8L7xQE

-

Evoke Therapy Programs & Reedy, B. (2023, June 10). Getting my spouse to do their work (Q&A) [Video]. YouTube. https://youtu.be/FI7ePeXjvug

-

Johnson, J. [@_jasonjohnson]. (2015). The birth parents we struggle to show grace to today were likely the kids 20-30 years ago we would [Tweet]. Twitter. https://twitter.com/_jasonjohnson/status/611190867932672000