Single Parent Adoption: The Process and Experience of Adopting Unpartnered

Adoption Advocate No. 159

An increasing number of adoptive families are single parent households where children have found permanency and are thriving with a Mom or Dad only. To learn how to best support these adoptive families, and provide guidance for singles considering adoption, we spoke with experienced single adoptive parents to understand their process and learn from their expertise. This issue of the Adoption Advocate also includes important tips for professionals in assessing single prospective adoptive parents and assisting them pre and post adoption.

Introduction

The dominant image of adoption in the United States features a husband-wife team, usually white and middle-class, surrounded by or holding the new members of their family. According to data collected by the Department of Health and Human Services and the Department of State, it is the case that white, married couples have accounted for the majority of adoptions by Americans, in part because these individuals are a majority in the general U.S. population.

However, sociocultural changes since the 1960s and 1970s have sanctioned, in terms of both legal allowance and community approval, adoption by other families.[1] Gradually growing acceptance of various family configurations in the 21st century has resulted in greater recognition of different types of adoptive parents. Among these are single men and women.

History

The Massachusetts Adoption of Children Act in 1851, the first modern adoption law, marked the beginning of a century of quantitative growth and legislative recognition of adoption in the United States. Over the decades, adoption professionals have worked with legislators to institute standards to protect the rights of birth families, adopted children, and prospective adoptive parents.[2]

International adoption as it is known today dates back to the years after World War II.[3] International adoption policies related to singles have not been static; in some countries, like China, child welfare has shifted from allowing single-parent adoption to practically banning it to allowing it again.[4],[5],[6] In other countries, like Bulgaria, policies have remained the same for decades.[7] Concurrently, while no explicit law has existed in the United States banning adoption by singles, and marital status has not been a sufficient basis to deny an adoption petition, a preference toward married couples has at times hindered adoption by unpartnered men and women. Single women did adopt in the early 1900s, but they were not as socially accepted, being regarded as less desirable parents because of their marital status; single men met with more scorn and suspicion.[8],[9]

In the 20th century, court decisions often demonstrated preference for married couples over single parents. The 1972 case of “Baby H” in New York, for example, concluded with the removal of the infant from her single caretaker’s home for placement with a Mr. and Mrs. M per the interpretation that “the benefit to Baby H of removal from petitioner is clear, unequivocal and major” based on the caretaker’s financial and social position.[10] Statements from government officials and organization leaders also discouraged single-parent adoption. When the Los Angeles Bureau of Adoptions launched the first program to recruit single parents for foster care and adoption in 1965, the director Walter E. Heath stated that while two parents were preferable, “one parent is better than none.” Two decades later, Governor Michael Dukakis of Massachusetts instituted a policy of placing children only in “traditional family settings”, meaning “with relatives, or in families with married couples, preferably with parenting experience and with time available to care for foster children.”[11]

Since the 1970s, the number of single-parent households in the United States has increased, and this population-level change has helped to smooth the paths for single adults pursuing adoption. From 1980 to 2008, the number of single-parent households grew from about 6,000,000 to a little over 10,000,000, accounting for over 25% of households with children.[12] Advancements in the industrial economic model, late 20th century struggles for gender equality, the entrance of women into the job market, higher divorce rates, development of contraceptive methods, and changes in societal values have contributed to the rise of single parenthood.[13]

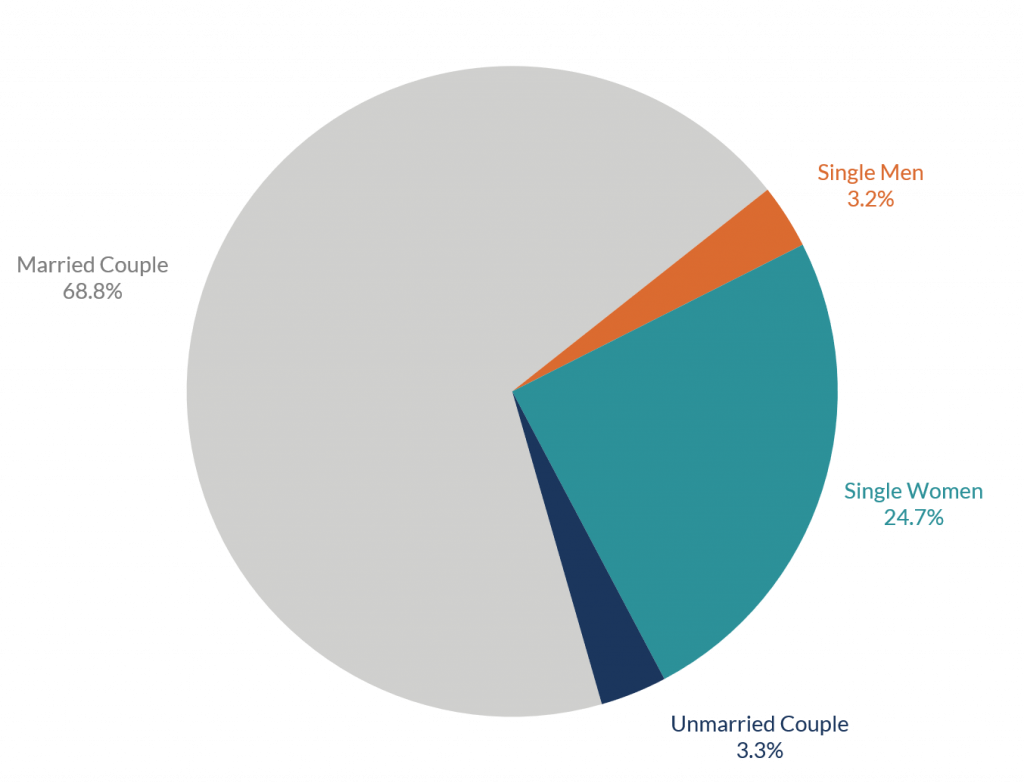

Greater acceptance and opportunity are reflected in national adoption statistics. Based on data from the Adoption and Foster Care Analysis and Reporting System (AFCARS), singles made up about 28% of all parents adopting from U.S. foster care in 2017-2019.[14] For comparison, estimates for single-parent adoption in the 1970s range from 0.5% to 4%.[15] In intercountry adoption, according to data from the 2007 National Survey of Adoptive Parents, single parents constitute a smaller slice of the adoptive parent pie; married couples account for a high 82%.[16]

Adoptive Family Structures (2017–2019)

Research on Single-Parent Households

The increase in the number of single-parent households has mitigated some fears about them, but the concern persists that the absence of two, opposite-sex parents in the house will be a significant detriment to children.[17] Alfred Kadushin, criticizing the reception of single-parent adoption among social workers in 1970, suggested, “Perhaps the greatest component of the social worker’s ambivalence and discomfort about single-parent adoption...is based on a dubious equation...that the single-parent family is likely to be a pathogenic family.”[18]

Stigmas about Single Parents: From the 1970s On

Speaking specifically about single mothers, the “hypothesized difficulties” of fatherless children have been regarded as numerous, indirect, and direct.[19] On the former point, it is supposed that single mothers have less physical and psychic energy for their children as a consequence of not having a male partner. The claim is that she lacks emotional support, sexual satisfaction, companionship in leisure time, assistance in home and childcare, and a fellow decision-maker. On the latter point, it is supposed that children suffer socially and emotionally as a consequence of not having a father. They lose an intimate source of masculine identification, an additional disciplinarian, companionship, and opportunity to observe an ongoing marriage; moreover, they are relegated to a minority group of fatherless children.[20]

Regarding single fathers, the common portrayal both in media and in the public psyche casts them as the subordinate parent: inept, lacking in the natural parental instincts, and unable to so much as dress their children properly.[21] Unaided by female direction, the suggestion is that they will perform poorly when placed in a single parent role. Joe Toles, a father to seven sons through foster care, shares that he delayed the building of his family until his late 40s/early 50s because he had bought into “societal expectations” that he needed a wife to provide a home.[22]

Compared to single mothers and same-sex couples, single fathers receive less attention in research. This absence is explained in part by the assumption that single, straight men have no innate desire to raise children without the direction of a female partner, and thus present no legitimate case for sociological study.[23] This perception arises even as the number of single father-headed households has increased in 50+ years, representing about one-quarter of all single-parent households in the United States in 2013 as compared to the less than one-sixth in 1960.[24]

Countering the Stigmas

One of the challenges of evaluating these common beliefs about single parenthood is the difficulty of research reproduction in the sciences, and particularly in psychology and sociology.[25] Moreover, whatever findings are drawn from the experiences of parents made single by separation from or death of the other spouse, or from the absence of a steady partner to begin with, cannot be seamlessly translated to predict the experiences of single parents made so by conscious adoption decisions.

What can be addressed is the stigmatization of single mothers and fathers that stems from the belief that proper child development hinges on the presence of both female and male parental figures and that the absence of one leaves the other with an unamendable deficit. This criticism supposes that the decision to raise a child as a single man or woman, whether by circumstances beyond one’s control or not, is unjust to a child because the removal of a mother or a father will inevitably starve them of some element embedded in the male-female pairing.

Cindy Morrison, a single mother to five daughters through intercountry adoption, is no stranger to this belief. She recounts the obstacles she has faced as a single adoptive mother with teachers who, following societal assumption, planned class activities and events with two-parent, opposite-sex households in mind, such as father/daughter dances. Morrison explains, “Each year I would remind teachers that my daughters are part of a single parent household, so activities such as Father's Day gifts needed to be modified.”[26]

The ideal circumstance for a child is in the home of their birth family. However, this does not exclude the possibility of good—and, in many instances, greater—circumstances in other family configurations.

The first obstacle was getting past my own notion that the "perfect" family included a mom and a dad. While the "ideal" family probably still does, I have learned that there is NO such thing as a "perfect" family, and that a single-parent home is vastly better for a child than growing up without a family. In some cases, in fact, a single parent home is actually preferred for a child who has experienced certain kinds of trauma.

Joleigh Little, adoptive mother to two

Improper interpretations of and inferences from social science research on family configuration and children’s outcomes have made gospel the belief that a child can fully thrive only in a household with a married, opposite-sex couple. This is not to say that such a family structure is negative; indeed, for much of the history of Western civilization, the husband-wife-children unit has prevailed for the perpetuation of tradition and society, and the pursuit of this remains the goal of many. It is to say, though, that non-traditional family structures can also provide the love and stability that children need.

The Adoption Process

Decision to Adopt

The adoption process begins with the decision to adopt. For some, adoption has been a dream since childhood, as it was for Cindy Morrison, who expressed her interest in adoption to her friends and family early in life. For Rachel Yoder, a single adoptive mother of five from foster care, the desire to adopt arose at age 9, when she read Seed from the East, by Bertha Holt, as well as books like No Crying He Makes, by Miriam Lind and The Family Nobody Wanted, by Helen Doss.

One’s social network could be the first obstacle in the adoption process. Despite numerous advances made in the last century regarding public perception of adoption, including a heightened awareness and boldness of discourse regarding the process and its implications, misunderstanding, doubt, and even some animosity lingers. Any prospective adoptive family may face friends and family who wonder if they could love a child that wasn’t biologically tied to them or if they could handle the traumatic background with which an adopted child might come to them. Adoption continues to have “second best” status among some, which adoptive families regularly have to repudiate through their adoption narratives.[27]

For singles, additional pushback may arise on the basis of marital status. Objections may hinge on the stigmas surrounding single motherhood and single fatherhood addressed previously. Family members may question why the prospective parent doesn’t wait for the right partner before starting a family. Joleigh Little was asked by her immediate family whether she had “thought this through.”[29]

After the decision to pursue adoption, prospective adoptive parents have three main avenues by which to adopt: foster care adoption, intercountry adoption, and private domestic adoption. Whichever path the prospective parent chooses, Little stresses the importance of finding an adoption agency that accepts single parents as clients and prioritizes post-adoption support. It took several hard no’s from agencies to which she initially applied before Little discovered a welcoming agency for her single parent adoption.

Assessment of Prospective Single Adoptive Parents

Sue Orban, an experienced adoption professional, states that the assessment of single applicants is similar to that of couples in terms of family support, financial capacity, and other factors. She suggests asking single applicants questions such as “Who are you going to call in the middle of the night if you have to go to the hospital?”, “Do you have the flexibility with your job for doctor’s appointments, school meetings, emergencies?”, “Do you have a child care plan?”, “How long are you able to stay home during the time of adjustment?”, and “What if you need to stay home longer?”[30]

These questions confront the reality of single parenthood, with the challenges that being unpartnered bring. During the probing evaluations by child welfare agents involved in the adoption process, the main goal is not to further complicate the process or to discriminate against singles, but rather to certify that a prospective single parent is aware of and prepared for the challenges of raising an adopted child in their non-traditional circumstances. There are three main considerations: social support, financial stability, and job flexibility.

Strong Social Network

First, single parents should demonstrate that their family will have a strong social network, whether of extended family or close friends, to support them post-adoption and as their child matures. While all parents need a support system, it is especially important for a single parent who does not have a partner to assist with childcare when they are at work or ill or when basic parental fatigue strikes and the parent needs backup.

During the adoption process itself, Orban strongly encourages a support person from one’s social network to join during travel, if applicable, and for some time after returning home, helping the new parent bond with their child by lightening their errand load and providing opportunities for rest in the beginning. When Little was adopting her first daughter, she worked alongside a single father friend who was adopting at the same time.

In sociology, a concept called the microstructural paradigm highlights the ability of single parents to fulfill typical maternal and paternal roles based on the impact structural positions have on parenting practices and the importance of interactional and situational factors, and not merely socialization and biology, in shaping behavior.[31] When he adopted his sons, Toles recognized that, though they “had no relationship with their fathers,” there were ”some hesitations/uncertainty of how to deal with a male parent figure” and a consequent desire for a female parent figure.

“Having had the same experience,” Toles continues, speaking as a former foster youth, “I had doubts about my ability to interact in such an intimate way with teens who I could engage [with] from a professional standpoint....They all missed their mothers…. It took a minute for them to give up what they were looking for in a female surrogate and accept a male substitute. I cannot do what a ‘mommy’ can do to the emotional state of a child. We work at making that part of our relationship work.”[32] The efforts to fold into his parenting that emotional supportiveness associated with mothers is in line with the microstructural hypothesis. This adaptation, however, does not nullify the importance for children to be in regular contact with members of each sex.[33] Hence, beyond assistance in routine tasks, male family members and friends in a single mother’s circle can provide male role models for their children; likewise, female family members and friends in a single father’s circle can provide female role models.

On the social network front, Julia Norris, an experienced adoption professional and a single adoptive parent herself, recommends that single-parents-to-be consider relocating near family both for the support and the opportunity for the adoptive child(ren) to develop close bonds with other family members.[34] Speaking to other adoption professionals, Amy Imber, Executive Director of Connecting Hearts Adoption Services, adds, “Being a mom or dad is challenging with a partner, so parenting without a partner has another layer of challenges. Discussing who they trust and can count on in a pinch and [who can] encourage the potential adoptive mom or dad to approach their friend or family member before bringing a child home is imperative.”[35]

When my children were little and cute, the admiration and support from the community and my extended family was amazing. We would show up to church on Sunday morning...looking all clean and sweet and nicely dressed and I sat in the pew with my five little kids of all colors and special needs. Everyone likes a positive feel-good story and we were a nice little example of that and everyone wanted to have a part in it. However...my children got older and bigger. They were no longer so little and cute and cuddly. They had problems. Big problems.

Rachel Yoder, single adoptive mother to five[36]

If possible, one might consider including in this support network adults who are familiar with adoption matters, like the Seven Core Issues in Adoption[37] and the psychological and behavioral impacts of childhood trauma. These could be fellow adoptive parents, adoption professionals, psychologists, and others who would be willing, as well as emotionally and practically able, to continue materially supporting the single parent’s family as their children grow up.

Beyond physical connections, social media, like adoption-specific Facebook groups, has provided new ways for adoptive singles to interact with a national, and even international, conference of similar families for support and encouragement. Yoder celebrates, “So now we no longer have only the people physically surrounding us to give us support but we have the world at our fingertips! I treasure my online friends tremendously! We have found community online in ways that [are] impossible...in real life.”[38]

Financial Stability

Second, single parents should demonstrate their financial stability. This is, of course, a desired characteristic of all prospective adoptive families, but the assessment is slightly different for singles. In single parent adoption cases, the family will rely on a single income earned by a single person on whom the responsibilities of breadwinning and homemaking are both fully laid. This is distinct from married couples in which, oftentimes, each partner takes prime responsibility for one of the roles or both work either part-time or full-time.

While a bank account overflowing with cash is certainly not required to adopt, prospective single parents should have sufficient resources to meet the expenses involved in raising a child or children once the adoption is finalized, to say nothing of the possible costs incurred during the adoption process. Intercountry adoption, for one, has expenses averaging between $20,000 and $40,000 for agency fees, dossier preparations, travel, and other items.[239] Apart from these actual adoption expenses, the sending country typically has financial requirements that depend on the income and net worth of the applicant, for which single parents may be more closely scrutinized.

In addition to a stable income, Norris emphasizes preparation of an emergency fund to buffer their families in the event of job loss or other unforeseen circumstance.

The U.S. Department of Agriculture estimated that a single-parent household with one child spent between $11,500 and $13,500 on child expenses in 2015, and about $8,000 more with two children.[40] These estimates are population-wide, and do not detail possible additional expenses such as counseling with an adoption competent mental health professional—which adopted children may need in order to adapt and thrive—but do include childcare costs. According to a 2017 report from Child Care Aware of America, childcare for infants, toddlers, and four-year-olds accounts for an average 10% of married couples’ household incomes and 36% of single persons’ household incomes, with a national average cost of between $8,600 and $8,700.[41]

Given the financial requirements to help a child thrive, single adoptive parents are often older and, presumably, more established in their careers and financially stable. Considering just foster care adoption in the United States, in 2017-19 AFCARS recorded that over 50% of single adoptive parents were in their 40s and 50s, though single parent adoption by younger individuals in their 20s and 30s and older individuals in their 60s and 70s did occur at not-insignificant frequencies. For instance, Rachel Yoder began fostering at 22 and Cindy Morrison completed her first adoption at 32.

Job Flexibility

Third, single parents should demonstrate job flexibility. Is the parent’s current career compatible with parenthood unassisted by a significant other? Imber recommends that the prospective parent preliminarily explore “how their employer will (or won’t) support them and/or offer flexibility.”[42] For prospective single parents, more than married couples, for whom there is a higher likelihood of availability between the two, having a family-friendly work situation is crucial. That is, they would benefit from being in a job that allows them to, for example, leave work to address problems at school or attend appointments, work from home in the event of illness, and, if desired, advance in their career without having to sacrifice their home life.[43]

Non-traditional work situations, like part-time or freelance jobs and working from home, lend more opportunity for schedule flexibility. Little, for instance, has worked for decades for an organization, Wisconsin Right to Life, that is adoption-supportive. Her role lets her work from home, and the child- and adoption-friendly atmosphere has allowed her to travel with her daughters to whatever outside tasks and events her job requires. Through this work, her family has gained an “incredible extended family that stretches from our little village in Northern Wisconsin to the southern part of our state and beyond that to Washington, D.C., with tentacles reaching into all 50 states” that have lent home and career support in addition to flexibility.[44]

When financial stability depends on traditional full-time occupation, one could discuss schedule accommodations and family-friendly benefits with their employer in preparation for the hard work of parenting. In her case, Morrison credits the “huge amount of flexibility” in her previous and current employment positions—before as a pediatric occupational therapist, now as founder and executive director at a non-profit for vulnerable children in China—for enabling her to adopt and support her large family.[45]

To gauge the plausibility of melding one’s current career with parenthood, it may help prospective single parents to calculate the hours they spend working, commuting, and sleeping and add to that daily or weekly breakdown the hours they expect to spend performing routine parenting activities, like cooking and cleaning.[46] Other expenses to hypothetically account for are additional services to ease the transition and facilitate the development of an adopted child. For open private domestic or foster care adoptions, visitation days will be another consideration.

As time passes, an adoptive parent may have to change the trajectory of their work life to accommodate the needs of their child(ren), as Yoder did when her clan grew with the addition of foster and adopted youth who presented with significant medical needs. After working part-time on and off, babysitting, and engaging in other work-from-home options, she shifted to full-time foster care, with adoption stipends and med-level foster care rates providing the primary income for her family.

Beyond these circumstance-specific considerations, prospective single parents follow the general steps and assessments that apply to everyone pursuing adoption, including adoption training and education, cultural education in the case of transracial adoption, and support system buttressing.[47] The time between application and placement varies depending on, among other factors, whether the prospective parent opts for foster care, intercountry, or private domestic adoption and on the ages and special needs the parent specifies being comfortable handling.

Single Adoptive Parenthood

Expectations Versus Reality

Honestly, it’s been a thousand times harder than I could ever have imagined. When you’re young and have big dreams and lots of energy, it looks possible to do anything, including changing the world. There is just no way for a new foster or adoptive parent to grasp the enormity of that parenting journey and there is no way to adequately prepare. You just take each day as it comes and meet each new challenge and find your way step by step.

Rachel Yoder, single adoptive mother to five[48]

By all means, prospective single adoptive parents should educate themselves on parenthood and adoption. Reality, though, will almost always transcend the best imagination. Adoption is not chemistry, where the combination of this solvent with that solute results in a scientifically calculated and confirmed result; adoption is the combination of human beings, with their unique personalities, temperaments, traumas, and beliefs, into a unit not conceived of before.

Yoder has had her share and more of bumps and bruises while weaving together distinct stories through adoption. Her children, all adopted from foster care, range in age from 11 to almost 23. They are a mix of boys and girls and have various medical and behavioral complications, including autism, Down syndrome, and attachment disorders. She admits, “There [were] a couple years I was sure my three oldest would all end up in psych hospitals or juvenile detention” but, through much hard work, endurance, and parental flexibility, “[t]hey have stayed in school despite huge challenges, they have jobs and stick to them faithfully. They love their family.”[49]

Blending Stories

As for adopting from two different countries[,] in general I would say that it has made our little family much more aware of the differences between cultures, but also the unity that comes from realizing that we are all part of the same human family. We are richer both as individuals and as a family for our connections with both Bulgaria and China.

Joleigh Little, adoptive mother to two

Beyond individual personalities, adoption as a blending of stories often involves navigation through different ethnic cultures and races. Adoptions of these types are referred to as “transracial,” “transcultural,” or “interracial.” The psychological, social, and even political research on transracial and transcultural adoption is extensive,[50] and not the focus of this piece, but it deserves some consideration given that single parents adopt children from foster care with races different from theirs at about the same or higher rates as married couples[51] and that international adoption by parents in any family structure likely entails a transracial adoption arrangement.

At the time of her daughters’ adoptions, Little was single, though she has since married her husband, an experience she likens to adoption in that both necessitate adaptations in one’s life and household to accommodate a new human. For Little, single parent adoption has given her a deeper appreciation for family diversity, cultural differences, and shared humanity. Her first daughter, born in Bulgaria, traveled with her to finalize the adoption of her second daughter in China, where they received a “crash course in Chinese culture” that has better equipped Little to keep her Chinese-born daughter connected to it and her whole family involved with it. She calls this ability to build her diverse Bulgarian-Chinese-American family with bonds as close and strong as, and perhaps closer and stronger than, those forged through biology “one of the true miracles of adoption.”[52]

Decision Fatigue

I think the greatest challenge of single parenting is that, at the end of the day, I am solely responsible for making all decisions regarding my daughters. There are times I think it would be easier to have a husband to help make these decisions. Because of this challenge, I have learned to seek the guidance of friends and family to help make the best decisions possible.

Cindy Morrison, single adoptive mother of five[53]

Most single parents, adoptive or otherwise, mention the absence of a fellow decision-maker as one of the hardest aspects of parenting solo. It was among the “hypothesized difficulties.” The decisions that parents have to make are as small as knowing what snacks to provide with lunch and as large as choosing a school for their children to attend. Single adoptive parents may also have to decide on how much to tell their children about their adoption stories, how to maintain contact with birth parents and to what extent, what teachers and other professionals need to know about their children to provide adequate services, how to answer questions from nosey strangers about their family and “missing spouses,” when a behaviorally challenging child needs outside assistance and intervention, and more. In international adoptions like Morrison’s and Little’s, decisions about acculturation versus assimilation must also be made.

Married couples have the benefit of two adults to share the burden of decision-making. Morrison, whose five Chinese-born daughters range in age from 7 to 19, depends instead on her family and friends to talk through decisions for her family. This helps mitigate the risk of decision fatigue, a psychological phenomenon described in reference to “the impaired ability to make decisions and control behavior as a consequence of repeated acts of decision-making.”[54] This hearkens back to the cruciality of a strong support system during the family evaluation/home study period for singles considering adoption. For Morrison, outsourcing decisions and tasks has enabled her to focus more on building relationships and navigating trauma with her children.

A Lifelong Journey

My life and educational experiences have been an endless blessing to me. I am very self-reflective so “the little boy that I was” informed me of my youthful dreams and wishes while the man I have become provides the task-oriented practical answers that I need. I am blessed to have a real comfort in who I am and what I can do which allows me to reach out to friends and families who know me well.

Joe Toles, single adoptive father to seven[55]

Adoption does not end with the signing of papers and a court order; adoption is a process that lasts a lifetime. As children grow and mature, they develop a deeper understanding of “their relationships, sex, marriage, the idea of sacrifice, the idea of adoption having a dual nature, etc.” that impacts their opinions and ideas about adoption and their unique adoption story.[56],[57] As adoptive parents grow into their roles and a better understanding of their children, they may also shift their beliefs about and/or approaches to parenting, adoption, special needs and more regarding their family.

Joe Toles emphasizes the importance of continually reflecting on and learning from his life and educational experiences to parent his sons and of understanding himself well enough to know when to rely on the knowledge of others. He describes himself as “a real lifelong learner” who takes advantage of parent training sessions and issues forums and stays involved in mentoring communities where he both shares his experiences and advice on adoption and learns from the experiences and advice of others.[58]

Conclusion

Changes in child welfare policies, insight from sociological research, and general social shifts in the past few decades have encouraged higher rates of single parent engagement in foster care and adoption, but the greater ease of single parent adoption in the 21st century compared to the 20th century does not imply a greater ease of parenting itself. Yet despite the difficulties, parenthood can be and often is a highly rewarding experience.

Like adoption by a married couple, adoption by a single man or woman requires extensive circumstantial assessment and self-evaluation to determine whether their household and lifestyle can support the development of an adopted child who has needs similar to any other child as well as additional needs, such as early trauma, arising from their unique background. The adoptive parents should be prepared for the unexpected challenges that are inevitable for any parents and for the everyday challenges of parenting solo. Families should enter with optimism, with eyes wide open, and with the knowledge that it is challenging but undeniably possible.

Special Acknowledgement

Many thanks to the adoptive parents Joleigh Little, Cindy Morrison, Joseph Toles, and Rachel Yoder for their willingness to share with the National Council For Adoption parts of their personal, intimate stories on single adoptive parenthood.

References

[1] Kahan, M. (2006). “Put up” on platforms: a history of the twentieth century adoption policy in the United States. The Journal of Sociology & Social Welfare 33(3:4), 51-72. https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/jssw/vol33/iss3/4.

[2] Herman, E. (2012). Minimum standards. The Adoption History Project. https://pages.uoregon.edu/adoption/topics/minimumstandards.htm.

[3] Lovelock, K. (2000). Intercountry adoption as a migratory practice: a comparative analysis of intercountry adoption and immigration policy and practice in the United States, Canada and New Zealand in the post W.W.II period. The International Migration Review 34(3), 907-949. https://www.jstor.org/stable/2675949.

[4] Rouvalis, C. (2007). China’s wide-open adoption door closes. Post-Gazette. https://www.post-gazette.com/life/lifestyle/2007/01/21/China-s-wide-open-adoption-door-closes/stories/200701210151.

[5] China open adoptions to single women!!!!!! (2011). Creating a Family. https://creatingafamily.org/adoption-category/china-open-adoptions-single-women/.

[6] Jones, J. (2018). Can single parents adopt? If so, from where? Gladney Center for Adoption. https://adoption.org/can-single-parents-adopt.

[7] Tarr, L. (2018). A spotlight on adoption from Bulgaria! Nightlight Christian Adoptions. https://mljadoptions.com/blog/spotlight-adoption-bulgaria-20180214.

[8] Herman, Ellen. (2012). Single parent adoptions. The Adoption History Project, https://pages.uoregon.edu/adoption/topics/singleparentadoptions.htm.

[9] Seeman, M. (2018). Single men seeking adoption. World Journal of Psychiatry 8(3), 83-87. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6147772/.

[10] Matter of Infant H, 69 Misc. 2d 304, 330 N.Y.S.2d 235 (N.Y. Misc. 1972).

[11] Clendinen, D. (1985, May 25). Curbs imposed on homosexuals as foster parents. The New York Times, 24.

[12] See Table 1336. Single-parent households: 1980 to 2009 from the U.S. Census Bureau. https://www2.census.gov/library/publications/2010/compendia/statab/130ed/tables/11s1336.pdf.

[13] Biasutti, C. & Nascimento, C. (2021). The adoption process in single-parent families. Journal of Human Growth and Development 31(1), 47-57. http://doi.org/10.36311/jhgd.v31.10364.

[14] United States. (2017, 2018, 2019). The AFCARS report. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Dept. of Health and Human Services, Administration for Children and Families, Administration on Children, Youth and Families, Children's Bureau; United States.

[15] Kreider, R. (2003). Adoptive single parents and their children: 2000. United States Census Bureau. https://www.census.gov/wp-content/dam/Census/library/working-papers/2003/demo/adoptive-single-parents.pdf.

[16] Vandivere, S., Malm, K. & Radel, L. (2009). Adoption USA: a chartbook based on the 2007 National Survey of Adoptive Parents. Washington, D.C: The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation. https://aspe.hhs.gov/system/files/pdf/75911/index.pdf.

[17] Sencer, M. (1987). Adoption in the non-traditional family--a look at some alternatives. Hofstra law review 16(1), 191-212. http://scholarlycommons.law.hofstra.edu/hlr/vol16/iss1/8.

[18] Kadushin, A. (1970). Single-parent adoptions: an overview and some relevant research. Social Service Review 44(3). https://www.jstor.org/stable/30021711.

[19] Ibid.

[20] Ibid.

[21] Brown, M. (2019). Single moms vs single dads: examining the double standards of single parenthood. Parents. https://www.parents.com/parenting/dynamics/single-parenting/single-moms-vs-single-dads-a-look-at-the-double-standards-of-single-parenthood-how-we-can-do-better/.

[22] Joseph Toles, personal communication, June 29, 2021.

[23] Seeman, Mary. (2018). Single men seeking adoption. World Journal of Psychiatry 8(3), 83-87, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6147772/.

[24] Livingston, G. (2013). The rise of single fathers. Pew Research Center. https://www.pewresearch.org/social-trends/2013/07/02/the-rise-of-single-fathers/.

[25] Barajas, M. (2011). Academic achievement of children in single parent homes: a critical review. The Hilltop Review 5(1:4), 13-21. https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/hilltopreview/vol5/iss1/4.

[26] Cindy Morrison, personal communication, June 14, 2021.

[27] Baxter, L., Norwood, K., Asbury, B. & Scharp, K. (2014). Narrating adoption: resisting adoption as “second best” in online stories of domestic adoption told by adoptive parents. Journal of Family Communication 14(3), 253-269. https://doi.org/10.1080/15267431.2014.908199.

[28] Joleigh Little, personal communication, July 6, 2021.

[29] Joseph Toles, personal communication, June 29, 2021.

[30] Sue Orban, personal communication, June 10, 2021.

[31] The microstructural paradigm can be further explored in:

- Biblarz, T. & Judith, S. (2010). “How does the gender of parents matter?” Journal of Marriage and Family 72, 3-22. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/j.1741-3737.2009.00678.x.

- Coles, R. (2015). “Single-father families: a review of the literature.” Journal of Family Theory & Review 7, 144-166. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/jftr.12069.

- Hook, J. & Chalasani, S. (2008) “Gendered expectations? Reconsidering single fathers’ child-care time.” Journal of Marriage and Family 70, 978-990. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-3737.2008.00540.x.

- Risman, B. (1987). “Intimate relationships from a microstructural perspective: men who mother.” Gender and Society 1(1), 6-32. https://www.jstor.org/stable/190085.

- Seeman, M. (1987). “Single men seeking adoption,” World Journal of Psychiatry 8(3), 83-87. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6147772/.

[32] Joseph Toles, personal communication, June 29, 2021.

[33] Krisch, J. (2017). The problem with diverse role models. Fatherly. https://www.fatherly.com/health-science/role-models-diversity-daughter-dad/.

[34] Julia Norris, personal communication, June 9, 2021.

[35] Amy Imber, personal communication, June 12, 2021.

[36] Rachel Yoder, personal communication, June 18, 2021.

[37] Silverstein, D. & Kaplan, S. (1982). Lifelong issues in adoption. Fair Families. http://www.fairfamilies.org/2012/1999/99LifelongIssues.htm.

[38] Rachel Yoder, personal communication, June 18, 2021.

[39] International adoption costs. (n.d.). Considering Adoption. https://consideringadoption.com/adopting/adoption-costs/international-adoption-costs/.

[40] Lino, M., Kuczynski, K., Rodriguez, N. & Schap, T. (2017). Expenditures on children by families, 2015. United States Department of Agriculture. https://fns-prod.azureedge.net/sites/default/files/crc2015_March2017.pdf.

[41] Child Care Aware of America. (2017). Parents and the high cost of child care. Child Care Aware of America. https://www.childcareaware.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/12/2017_CCA_High_Cost_Report_FINAL.pdf.

[42] Amy Imber, personal communication, June 12, 2021.

[43] Children’s Bureau. (2013). Adopting as a single parent. Child Welfare Information Gateway. http://centerforchildwelfare.fmhi.usf.edu/kb/AdoptParent/AdoptAsSingleParent2013.pdf.

[44] Joleigh Little, personal communication, July 6, 2021.

[45] Cindy Morrison, personal communication, June 14, 2021.

[46] Children’s Bureau. (2013).

[47] Ibid.

[48] Rachel Yoder, personal communication, June 18, 2021.

[49] Rachel Yoder, personal communication, June 18, 2021.

[50] For further reading, see: Lee, R. (2003). The transracial adoption paradox: history, research, and counseling implications of cultural socialization. The Counseling Psychologist 31(6), 711-744. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2366972/.

[51] United States. (2017, 2018, 2019). The AFCARS report. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Dept. of Health and Human Services, Administration for Children and Families, Administration on Children, Youth and Families, Children's Bureau; United States.

[52] Joleigh Little, personal communication, July 6, 2021.

[53] Cindy Morrison, personal communication, June 14, 2021.

[54] Pignatiello, G.A., Martin, R.J. & Hickman, R.L. Jr. (2020). Decision fatigue: A conceptual analysis. Journal of Health Psychology 25(1), 123-135. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6119549/.

[55] Joseph Toles, personal communication, June 29, 2021.

[56] Anderson, Kristin. (2019). Is adoption a lifelong process? Gladney Center for Adoption. https://adoption.org/adoption-lifelong-process.

[57] Cam Lee Small, MS, LPCC, discusses the evolution of the adoptive identity in Adoption Advocate No. 149, “The Impact of Adoption on Teen Identity Formation”, at https://adoptioncouncil.org/publications/adoption-advocate-no-149/.

[58] Joseph Toles, personal communication, June 29, 2021.

Originally published in 2021 by National Council For Adoption. Reprinting or republishing without express written permission is prohibited.