Openness in Adoptions: Satisfaction and Psychological Outcomes Among Birth Mothers

Adoption Advocate No. 133

Introduction

Historically, adoptions in the United States were strictly closed adoptions that entailed sealed legal records and absolutely no contact between the birth parents and the adoptive family (Cushman, Kalmuss, & Namerow, 1997). Open adoptions began occurring with more frequency in the 1980s and 1990s and are now more common than closed adoptions. This change in practice was driven in part by adoption professionals’ recognition that children who are adopted want to know more about where they come from and who their birth families are (Jordan, 2018). Features of open adoption, such as visiting and phoning the adoptive family, have a strong relationship with long-term positive outcomes for birth mothers (Cushman et al., 1997). Research shows that birth mothers who received letters and/or pictures reported higher levels of relief and significantly lower levels of worry compared to birth mothers who did not (Cushman et al., 1997). These positive outcomes are related to the birth mothers’ mental health as well as their overall satisfaction with the adoption process (Silverman, Campbell, Patti, & Style, 1988). Giving birth mothers the opportunity to be involved with selecting adoptive parents is also strongly associated with positive outcomes (Cushman et al., 1997). Considering the many positive outcomes of open adoptions, it follows that adoption organizations will want to know more about whether to encourage their clients to pursue open or closed adoptions.

Weber State University’s Community Research Team partnered with Forever Bound Adoption to learn more about birth mothers’ feelings on how openness, or lack thereof, affects birth mothers’ satisfaction and psychological outcomes with regards to the adoption process. We hypothesized that birth mothers who have had an open adoption will have higher levels of satisfaction and fewer negative psychological outcomes compared to birth mothers who have been involved in a closed adoption. Those psychological outcomes could be depression, anxiety, or other issues pertaining to the mind and mental health of birth mothers. We also looked at the satisfaction of birth mothers and measured it based on the mother’s level of grief or regret after her decision of relinquishment. This study targeted birth mothers who have made adoption plans for their children. Our community partner, Forever Bound Adoption, advertised the survey and recruited the participants using its networks of local adoption agencies and social media sites. By participating in this study, birth mothers were able to voice their feelings about their adoption experience in a completely anonymous way.

Literature Review

Due to adoption becoming a more common practice in the United States, there has been an increased effort to research the process (Jordan, 2018). Few studies have looked at the effects of voluntary relinquishment on birth mothers and the satisfaction with their choice (Silverman et al., 1988). A review of the adoption literature will turn up even fewer studies that have analyzed the experiences of birth mothers after the shift to open adoptions. Despite the consistent trend towards more openness in adoption, not all agree about the merits of such practices (Lyons, 1999). Some professionals advocate completely open arrangements, others continue to favor closed adoption, whereas others recommend the moderate semi-open approach which allows the exchange of some information. This semi-open adoption consists of some contact between birth parents and adoptive families, while still safeguarding the privacy rights of each party involved (Siegel, 2013). Furthermore, it has been found that the adoptive parents reported more positive feelings towards the adoption when they knew the birth parents personally (Siegel, 2013).

Previous research (e.g., Grotevant et al., 2007) has explored the different perspectives between families with no contact, stopped contact, contact without meetings, and contact with face-to-face meetings with adolescent and birth mother. Researchers interviewed the adoptive parents about their experiences as an adoptive family, their relationship with the adoptee, and their experience with members of the birth family, views about openness arrangements, and any hopes for the future regarding their relationship with members of the birth family. This study (Grotevant et al., 2007) looked specifically at the satisfaction of the adoptee, adoptive mother, and the adoptive father. Results showed that the two most common categories of contact were ‘no contact’ or ‘contact with meetings.’ The satisfaction was highest for all three groups that had ‘contact with meetings’ and was statistically significantly different for adoptees that had a very low satisfaction with ‘no contact’ (Grotevant et al., 2007). Due to the previous study not focusing on birth mother satisfaction, the present study sought to include birth mothers’ perspectives to examine their satisfaction with the adoption process.

Research has also focused on birth mothers’ reunions with their child, and their feelings related to the reunion. For example, Silverman et al. (1988) found that the majority of birth mothers who had a reunion with their adoptees believed an open adoption was the best choice. Few studies (c.f., Cushman, Kalmus, & Namerow, 1997; Silverman et al., 1988) have focused primarily on birth mothers and how openness could affect their adoption process, satisfaction, and their general psychological outcomes. By conducting this research, we hope to add more applicable knowledge to the process of adoption and help future birth mothers with their adoption decisions. We hope this study explains what the adoption process is like, directly from the birth mother’s point of view.

Objective

The goal for this project was to get a relatively large sample of birth mothers to determine whether having an open or closed adoption affected the satisfaction and psychological outcomes among birth mothers. Forever Bound Adoption of Utah was interested in this project to provide research to future birth parents. It also provides them with more information on whether having an open or closed adoption would be best for them. For this project, researchers utilized a social survey to gather qualitative data. This allowed the researchers to find out more about attitude, feelings, experiences, and opinions about the adoption.

The project was done by asking a different set of questions to help answer our main research questions: Does having an open or closed adoption affect the satisfaction of birth mothers? Does frequency of communication affect birth mothers’ satisfaction? Does having an open adoption agreement affect birth mothers’ satisfaction? How does the level of involvement in the selection of the adoptive family affect psychological outcomes among birth mothers?

Methods

For this research project we partnered with Forever Bound Adoption of Utah to learn more about the birth mother’s perspective of the adoption. The survey was a cross-sectional self-administered online survey that allowed us to gain participants from all over the United States. The survey asked a variety of questions including basic demographic characteristics, how open their experience with adoption was, the age of placement, year of adoption, type of adoption, etc. The questions from the survey were taken from different outside sources that were shown to be both internally and externally valid.

We asked these questions in order to understand if the amount of openness in the adoption affected the satisfaction and psychological outcomes among birth mothers. Forever Bound Adoption of Utah initiated the recruitment for our participants. This was accomplished by posting the survey’s link on their website while also reaching out to other adoption agencies around the country to help promote it. We calculated our sample size to be 144 participants, located throughout the United States.

Demographic Information of Participants

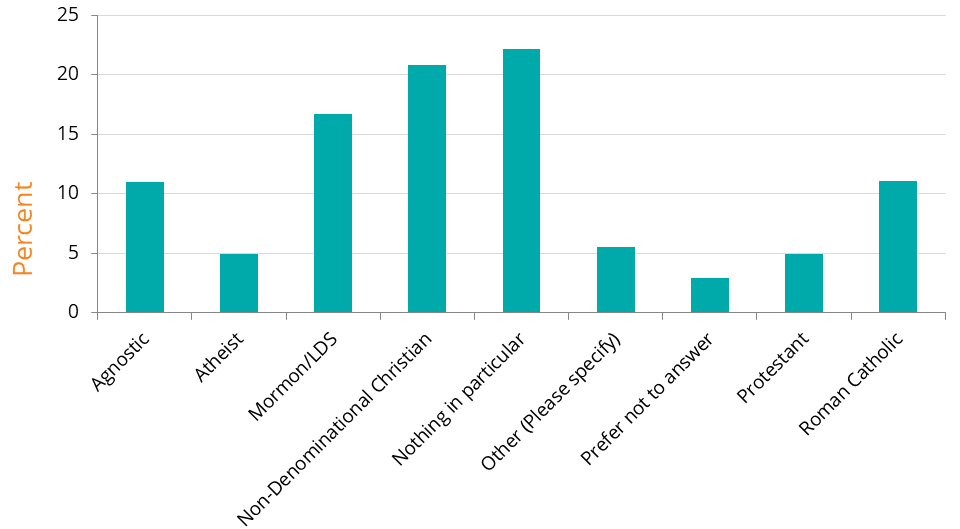

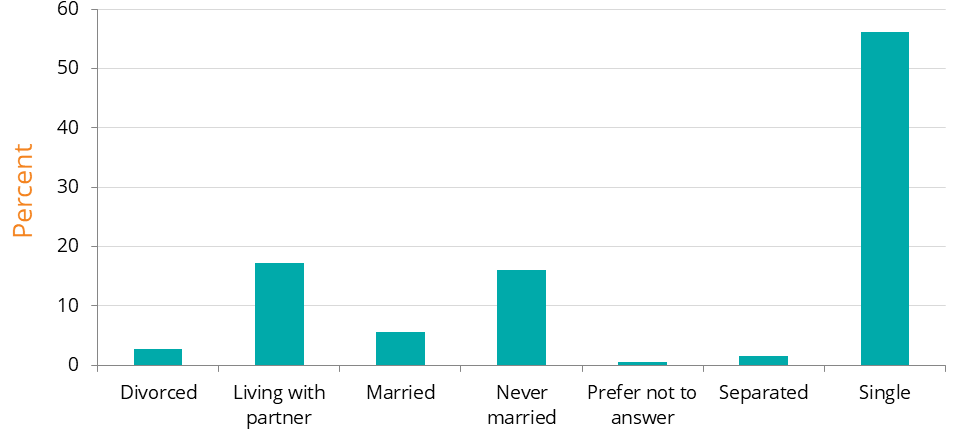

Our sample consisted of 144 birth mothers who have placed a child for adoption at some point in the past. By conducting our survey online, we were able to gain participants from outside of Utah. We broke down religion in different categories, which can be seen in Figure 1. We also asked participants their relationship status at the time of adoption, and those frequencies can be seen in Figure 2.

We also looked at the different ethnic groups of participants, which included the following numbers: American Indian or Alaskan Native=2, Asian=2, Bi/Multi-Racial=5, Hispanic or Latino=6, other=4, and White or Caucasian=125. Another interesting demographic question was regarding their employment status at the time of the adoption. The groups had a large variety throughout the answers: full-time homemaker=9, in school and not working=22, laid-off or on strike=1, other=10, retired=1, unable to work=5, unemployed=21, working full-time=46, and working part-time=29. The highest level of education at the time of placement was also asked, which also showed a variety of answers throughout the different groups. The groups were as follows: Bachelor’s Degree=11, Doctorate Degree (Ph.D. or E.D)=2, High School diploma or GED=49, Less than High School=23, Master’s Degree=5, Some College/Associates Degree=45, and Vocational/Technical Training (after High School)=9.

We also asked the participants who helped them arrange their child’s placement. The groups included: facilitator or intermediary who introduced them to the adoptive parents (if a private independent adoption) (N=5), independent attorney not affiliated with an adoption agency (N=29), licensed adoption agency (N=94), and other (N=16). We asked the participants how many children they are currently parenting or have previously parented. The groups included: 0 (N=51), 1 (N=24), 2 (N=26), 3 (N=25), 4 or more (N=15). We asked the participants their age at the time of adoption. The groups included the following: 15-18 (N=27), 19-25 (N=82), 26-30 (N=17), and 31-48 (N=12). We asked the participants what year they relinquished their child for adoption. The groups included: 1967-1980 (N=7), 1981-1990 (N=11), 1991-2000 (N=30), 2001-2010 (N=57), and 2011-2019 (N=57). The survey also asked participants the age of the child at the time of placement, and those groups included: 0-1 week (N=109), 1.1 week - 1 month (N=20), 1.1 month - up (N=11).

Data Analysis

A one-way ANOVA was conducted to evaluate the relationship between birth mothers’ satisfaction and their psychological outcomes related to their adoption. The independent variable, psychological outcomes, included the following subgroups: no change in mental health, mental health disorder before with none present, some mental health disorder(s) before with more presently, and none before with some mental health disorder(s) presently. The result was found to be statistically significant, F(3,138) = 3.39, p < .02. Follow-up t-tests were conducted to evaluate pairwise differences among the means. The Bonferonni method of comparison was chosen to correct for error. The results of these t-tests showed that the group of birth mothers with no change in mental health are statistically significantly different from birth mothers who had more mental health disorder(s) present after adoption, p < .016. The mean of the first group with no change (M = 3.63, SD = .16) was larger than the second group (M = 2.66, SD = .27). The means are calculated from the satisfaction scale of 1-5 with 1 being extremely dissatisfied and 5 being extremely satisfied with the adoption.

A one-way ANOVA was conducted to evaluate the relationship between birth mothers’ satisfaction and whether they had an open or closed adoption. The independent variable was open vs. closed adoption. The result was found to be statistically significant, F(1,140) = 26.62, p < .001. The mean of the birth mothers with open adoptions (M = 3.62, SD = .13) was larger than the birth mothers with closed adoptions (M = 2.16, SD = .25). The means are calculated from the satisfaction scale of 1-5 with 1 being extremely dissatisfied and 5 being extremely satisfied with the adoption.

A one-way ANOVA was conducted to evaluate the relationship between birth mothers’ satisfaction and the amount of contact with the adopted child. The independent variable, amount of contact, included the following subgroups: “I have never had contact with my child,” “I had contact in the past but it has stopped,” and “I have continuous contact with my child.” The result was found to be statistically significant, F(2,139) = 36.91, p < .001. Follow-up t-tests were conducted to evaluate pairwise differences among the means. The Scheffe method of comparison was chosen to correct for error. The results of these t-tests showed that the group of birth mothers who have never had contact with their child and the group who have continuous contact with their child are statistically significantly different from each other, p < .001. The mean of the group who has never had contact (M = 2.17, SD = .27) was smaller than the group who has continuous contact (M = 3.94, SD = .12). The results of these t-tests showed that the group of birth mothers who had contact but the contact has stopped and the group who has continuous contact with their child are statistically significantly different from each other, p < .001. The mean of the group who has never had contact (M = 2.11, SD = .22) was smaller than the group who has continuous contact (M = 3.94, SD = .12). The means are calculated from the satisfaction scale of 1-5 with 1 being extremely dissatisfied and 5 being extremely satisfied with the adoption.

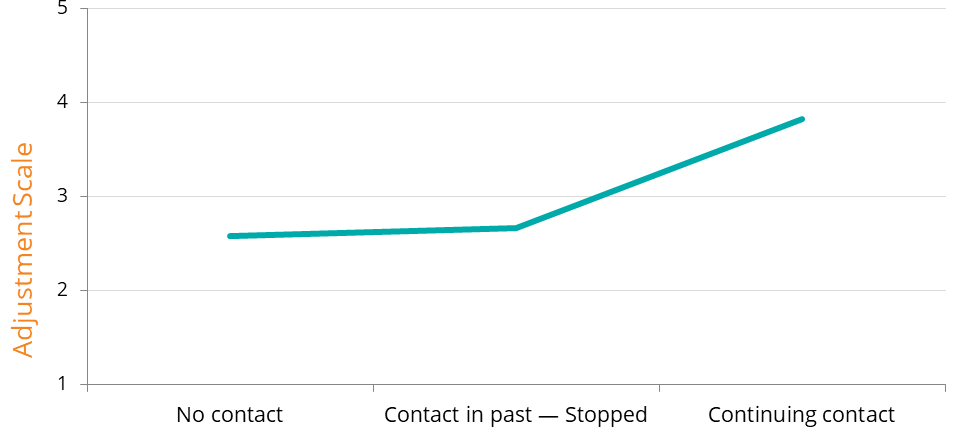

A one-way ANOVA was conducted to evaluate the relationship between the amount of contact with the adopted child and how the birth mothers felt they had adjusted to the decision to relinquish their child. The independent variable, amount of contact, included the following subgroups: “I have never had contact with my child,” “I had contact in the past but it has stopped,” and “I have continuous contact with my child.” The result was found to be statistically significant, F(2,140) = 12.40, p < .001. Follow-up t-tests were conducted to evaluate pairwise differences among the means. The Scheffe method of comparison was chosen to correct for error. The results of these t-tests showed that the group of birth mothers who have never had contact with their child and the group who has continuous contact with their child are statistically significantly different from each other, p < .002. The mean of the group who has never had contact (M = 2.57, SD = .31) was smaller than the group who has continuous contact (M = 3.83, SD = .14). The results of these t-tests also showed that the group of birth mothers who had contact but it has stopped and the group who has continuous contact with their child are statistically significantly different from each other, p < .001. The mean of the group who has never had contact (M = 2.66, SD = .25) was smaller than the group who has continuous contact (M = 3.83, SD = .14) which can be seen in Figure 3. The means are calculated from the adjustment scale with 1 being not well at all, 3 being neutral, and 5 being very well.

Limitations

The results of this study should be interpreted within the context of several key limitations. The sample size was distributed through an online self-administered study which could contain some bias due to it not being a large enough sample to apply to all birth mothers who have placed a child for adoption. Due to the survey being self-administered, some respondents may not feel encouraged to provide accurate and honest answers. Participants can provide information that may not accurately represent themselves, which can cause limitations on the reliability.

Future Research

The adoption process is very time consuming and complex and requires the involvement of many people. The primary people involved are part of the adoption triad, which consists of: the adoptee, adoptive parents, and the birth parents. Our project specifically targets birth mothers who have placed a child for adoption. Future research should be directed towards the other members, specifically the adoptive parents and the adoptee. More research can also be done on birth mothers and other factors that impact their satisfaction and look more in depth at their perspective of the adoption process. Future research can also reanalyze the data and compare the results to our own, to help with the accuracy of the findings.

Conclusion

The research question that drove our study was: Does the amount of openness in an adoption affect the overall satisfaction and psychological outcomes among birth mothers? Our hypotheses are supported by the research findings: open adoptions resulted in higher overall satisfaction and better psychological outcomes. Through our data analysis we found significant differences between birth mothers’ satisfaction and their psychological outcomes related to their adoption that showed the better the psychological outcomes the higher the overall satisfaction. We found significant differences between birth mothers’ satisfaction and whether they had an open or closed adoption that showed those with an open adoption had statistically significantly higher overall satisfaction. We found significant differences between birth mothers’ satisfaction and the amount of contact with the adopted child that showed those with continuing contact had statistically significantly higher overall satisfaction. We found significant differences between the amount of contact with the adopted child and how the birth mothers felt they had adjusted to the decision for relinquishing their child that showed those with continuing contact rated higher on the adjustment scale.

References

Agnich, L. E. Schueths, A. M., James, T. D., & Klibert, J. (2016). The effects of adoption openness and type on the mental health, delinquency, and family relationships of adopted youth. Sociological Spectrum, 36(5), 321-336.

Cushman, L. F., Kalmuss, D., Namerow, & Brickner P. (1997). Openness in adoption: experiences and social psychological outcomes among birth mothers. Marriage & Family Review, 25(1-2), 718.

Grotevant, H., Wrobel, G., Korff, L. V., Skinner, B., Newell J., Friese, S., & McRoy, R. (2007). Many faces of openness in adoption: perspectives of adopted adolescents and their parents. Adoption Quarterly, 10(3-4), 79-101.

Jordan, L. (2018). Is adoption good? Adopt a Baby.

Lyons, C. L. (1999). Adoption controversies. CQ Researcher, 9, 777-800.

Siegel, D.H. (2013). Open adoption: adoptive parents’ reactions two decades later. Social Work, 58(1), 43-52.

Silverman, P. R., Campbell, L., Patti, P., & Style, C. B. (1988). Reunions between adoptees and birth parents: the birth parents’ experience. Social Work, 33(6), 523-528.