Understanding Parental Postadoption Depression

Adoption Advocate No. 158

Postadoption depression. It’s more common than you may think, but it can be an uncomfortable thing for adoptive parents to talk about. Left unaddressed, postadoption depression, sometimes referred to as PAD, can lead to long-term struggles for both parent and child. In this month’s issue of the Adoption Advocate, you’ll hear from the foremost expert on PAD whose thoughtful and caring perspective offers hope and practical steps for dealing with this often overlooked issue in adoption.

Over a quarter century ago, the first description of postadoption depression appeared in the literature. In an article written in 1995, June Bond—author, adoption professional, and adoptive mother—was astute, sensitive, and knowledgeable enough to pick up on the dynamics of “postadoption depression syndrome or PADS” after the child was home. In essence, Bond noted how adoptive parents’ affect did not reflect the joy or happiness that she had expected to see as she performed post-placement home visits. There is now enough evidence to consider parental postadoption depression (PAD) an important area to discuss prior to and after adoption. Prospective adoptive parents may find this topic uncomfortable or even frightening to think about. Hesitations should be tempered by evidence that PAD affects some, but not the majority of parents. Estimates about how common PAD is vary widely, from 8% to 32% of parents.1 Several of these study findings are weakened by samples that may not represent all adoptive parents. In more recent studies, the highest rates of depressive symptoms were about 11% to 12% which may be a closer approximation of the actual rate of PAD.2 Thus, while PAD is not widespread, it is also not unusual.

Perhaps the most compelling reason to address the possibility of PAD is that evidence also suggests that if a parent is struggling with depressive symptoms the child may be affected in negative ways.3 More recent evidence suggests that paternal depression may be associated with children’s negative mood.4 So if a parent is wary about seeking help, motivation may stem from wanting to support the entire family, not just themselves. There are ways to mitigate and manage depressive symptoms, a point that may help assuage prospective and adoptive parents’ hesitations about PAD. Yet stigma towards mental health struggles still exists and many pre-adoptive parents want to ensure they present as competent, healthy, prospective parents to social workers and other adoption professionals, particularly when in the process of being approved to adopt a child.

The symptoms of PAD generally follow those of depression in general and include a depressed mood and/or loss of interest or pleasure in daily life.5 There can also be physical symptoms, such as a loss of or increased appetite, increased sleepiness or difficulty sleeping, or feeling fidgety and restless. Individuals may feel worthless, feel tremendous guilt, have difficulty concentrating, or think about death or harming themselves.6 Some adoptive parents who experience PAD report feeling “like a monster;” some panic and believe the decision to adopt may not have been correct, triggering a psychological crisis. For other parents, the symptoms of depression creep slowly into their beings. Please know that if thoughts of harming yourself or your child are present, this constitutes a crisis and professional help should be sought immediately.

As someone who has collected reports from hundreds of parents across studies, I know PAD may manifest itself in anger and helplessness and not knowing what to do about the emotions one is experiencing. Parents with PAD may be confused and “blindsided” by how they feel, and even question whether the decision to adopt was the right one. One common assumption in the adoption community is that the child’s ability to attach and bond to the parent may be difficult. The focus often is on the child’s attachment to the family, but we know that attachment involves a growing bond between parent and child. In certain cases of PAD, it may be the parent who is struggling to bond with child, especially if the attachment is not instantly formed. Parents should understand that “love at first sight” with the child is often not realistic, and that attachment is typically a a silent, sacred, and growing appreciation of a bond that builds through time and activities spent getting to know one another.

For a minority of adoption professionals, parental postadoption depression is still somewhat controversial, and there are researchers whose findings don’t support depressive symptoms after adoption.7 Some speculate that placement reduces depressive symptoms due to a reduction in psychological distress.8 I tentatively support the assertion that depressive symptoms can fluctuate pre-and post-placement, but there is more to the story. In the research I conducted with my team, we found that five classes or groups of 129 adoptive parents varied in trajectories of depressive symptoms across three time points: four to six weeks pre-placement; four to six weeks post-placement; and five to six months post-placement.9 For 71% of the parents in the study, no to few symptoms were reported at all three time points. Nineteen percent of the parents reported some depressive symptoms, but these symptoms were below the cut-off for a positive depressive screen. However, two classes were above the threshold of depressive symptoms at four to six weeks post-placement and three classes were above the threshold at five to six months post-placement.10 Again, while these groups are small, these vulnerable parents and families need support and understanding.

While comparisons with postpartum depression and PAD are often made, there are important differences. Aside from the obvious difference of giving birth and subsequent shifts in maternal hormones, risk factors in postpartum depression include marital and socioeconomic status, which have not been identified in PAD.11 In contrast, several studies that I have conducted found that unmet or unrealistic expectations parents held of themselves, of their child, of family and friends, and of society were predictors of depressive symptoms.12 My team has also discovered that the most difficult expectations to reframe are of ourselves as parents.13 Parental competency has also been cited as a risk factor in increasing parental anxiety and depressive symptoms.14 Evidence suggests that parents who have struggled with low self-esteem and depression prior to placement may be more vulnerable to psychological distress after the child is home.15 As mentioned, fathers as well as mothers may exhibit depressive symptoms after a child is placed in the home.16 Although we need more research studies with adoptive fathers and PAD, an exploratory study found that paternal predictors of PAD may revolve around slightly different areas than mothers. We found that the younger the child at adoption, lower relationship satisfaction scores, less perceived support from friends, and higher scores of unmet expectations of the child were predictors of paternal depressive symptoms.17

In sum, the evidence suggests that the majority of parents do not struggle with PAD, but the parents who do struggle need support and help—for themselves and their children. The expectations parents held prior to adoption may be precursors, when unmet or unrealistic, to depressive symptoms. Parental expectations of themselves as parents are the most difficult to change or reconcile when compared with expectations of the child, family and friends, and society. Fathers’ and mothers’ risk factors for PAD may differ. And the presence of parental depressive symptoms may vary depending on whether they occur pre- or post-placement of the child. Now let us consider some ideas for preventing or lessening the impact of PAD.

Mitigating PAD: Tips to Consider

The strategies below are not meant to be an exhaustive list, nor replace mental health services provided by a professional. The tips are a place to start as PAD is considered.

1. Do a Mental Health Check Before Placement

One adoption professional told me years ago that most, if not all, parents are exhausted at the end of the adoption process. It is so easy to become caught up in the process—the ups and downs—and hoping a child will be home with you soon. Despite this exhaustion, it is important to dialogue about PAD prior to placement. Several parents have reported that they wished they had heard of postadoption depression before experiencing it. Instead, they felt alone, isolated, and worried that they were the only parent who had experienced such emotions.

Some adoption agencies require prospective adoptive parents to identify support individuals, both personal and professional, during the adoption process, so the parent knows who they can seek support from if needed. If you are an adoption professional, consider whether your agency proactively requires prospective adoptive parents to identify personal and professional support individuals during the adoption process, so that parents know who they can seek support from if needed. Be sure to familiarize yourself with PAD so that you can ensure adoption-competent support to parents who may struggle.

If you are a prospective or adoptive parent, be honest with yourself if you have struggled in the past with anxiety, low self-esteem, and depression. What made you vulnerable to those emotions? What was helpful during those times to overcome those feelings? Along with this mental health check, be sure you have read, participated in training, and in general, prepared yourself to understand the dynamics of adoption. There are seven major issues that impact the adoption constellation, which includes the child, the birth parents and their extended family members, and the adoptive parents and their extended family members.18 To fully explore each of these areas is beyond the scope of this article, however, these areas are loss, rejection, shame and guilt, grief, identity, intimacy, and mastery and control.19 As importantly, parents should understand how thoughts and behaviors are associated with these themes. For example, for those who have been unable to build a family through having a birth child, has the grief over infertility been resolved? For those transracial adoptive parents, is there an awareness of racial identity for both the family and child? Kinship or relative adoptive parents may be especially challenged by the themes as intergenerational trauma may be present. It is important to take a strengths-based approach when discussing PAD, but to also emphasize that the journey of adoption begins when the child is home.

2. Do Surround Yourself with Adoption-Smart/Competent People and Professionals

The cultural practice of adoption is characterized by the fact that each child, each parent, each situation is unique. One adoptive parent may welcome a 15-year-old into their home from an out-of-home placement while another may parent an infant with special needs, relinquished from a 35-year-old successful executive. Other scenarios include an open adoption with frequent birth parent contact which, while constructed in the best interest of the child, can still trigger feelings of illegitimacy in the parent who is adopting. A kinship/relative parent may be grappling with an energetic toddler as well as being a cancer survivor, which adds to their fatigue and concerns about being a competent parent. A foster-to-adopt parent may experience depressive symptoms after being continually tested by a child to determine if the relationship is permanent. A competent adoption and mental health professional will be able to individualize the plan with the parent(s) to address the unique needs that may be contributing to depression.

A professional who understands this heterogeneity and the dynamics of adoption as well as trauma-informed care of children who have experienced psychologically distressing events (at any age), will be able to explain behaviors born from trauma. This individual can also help parents understand their own past traumas that may affect their parenting. Adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) have profound effects on our functioning in the adult world.20 ACEs indicate emotional and physical abuse and neglect as well as household dysfunction experienced by the individual during childhood (prior to age 18). Assessments of ACEs are “dose dependent,” in that the higher the ACE score or presence of abuse and maltreatment, the more likely an individual is to experience negative health outcomes, including depression and substance use. A professional will avoid uninformed reactions to the parents’ reports of depression and their child’s behaviors, and instead will be able to examine the family dynamics through a trauma-informed, adoption-competent lens.

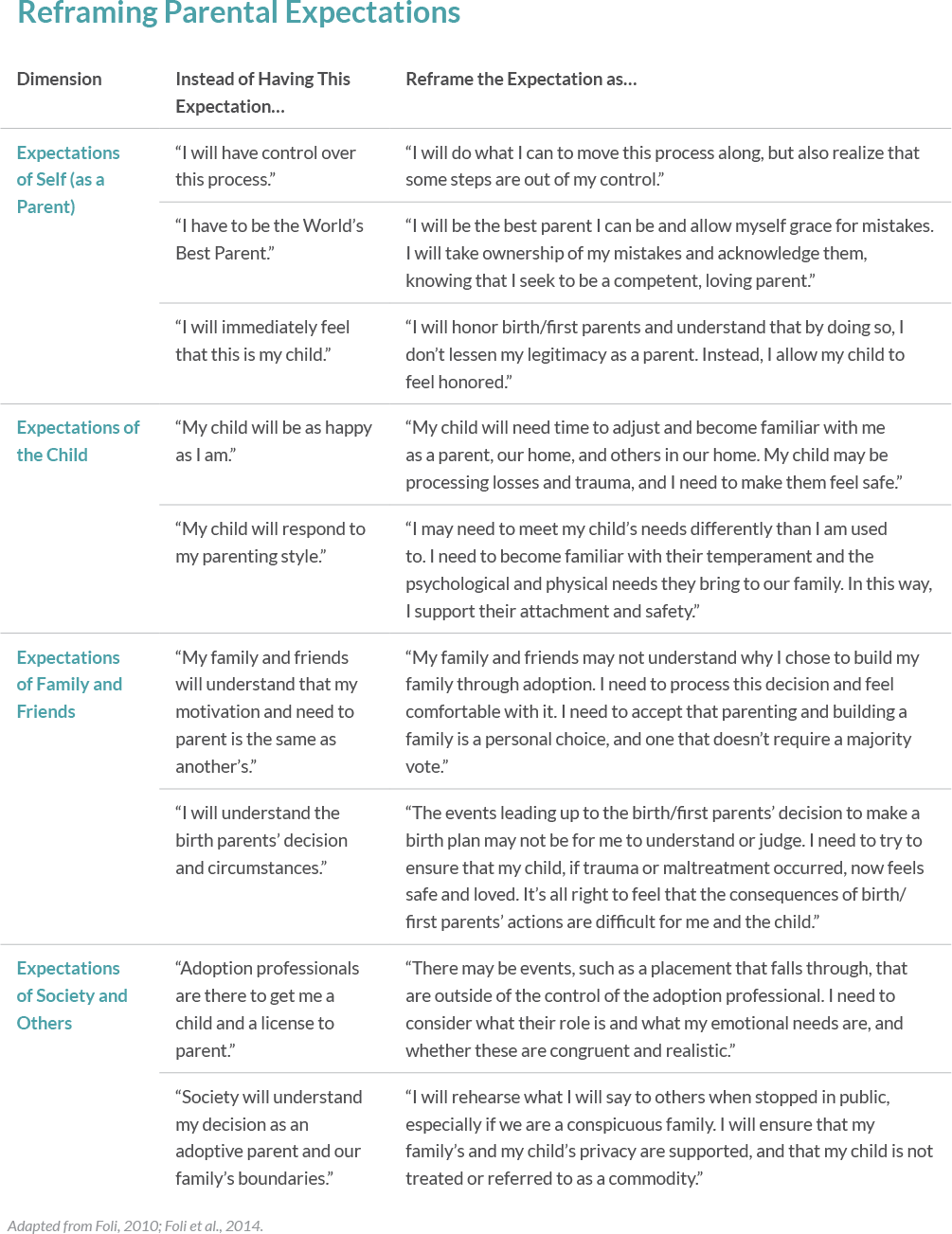

3. Do Reframe Expectations of Self, Child, Family and Friends, and Society

The information presented in “Reframing Parental Expectations” (see table below) builds on the theory of parental postadoption depression that depressive symptoms experienced by adoptive mothers and fathers may be associated with unmet and unrealistic expectations.21 Our cognitive processes are important to examine, and the thoughts we hold are at times precursors to our emotions and behaviors. By reframing these expectations, we allow ourselves to refocus our energies in new and positive directions.

4. Do Normalize Postadoption Support Services

When we think of parents who give birth, we readily understand that there will be support offered – from postpartum checks for the mother to instrumental support from family and friends (e.g., bringing food to the home, helping babysit siblings, and assisting with housecleaning). Emotional support for the postpartum “blues” is expected for both the mothers and fathers of newborns. In the same way, normalizing postadoption supports and tailoring such support to adoptive parents should be encouraged. The process of building a family continues long after placement. Martin and Rosenhauer compared parents who adopted children with special needs to parents who adopted children from China without diagnosed medical needs.22 Those who adopted children with special needs reported positive adjustment while parents of children without special needs reported more depression, anxiety, and problems with adjustment. The authors speculate that special-needs parents may be more prepared and receive more support than parents of children without special needs.23 These findings should be tempered by the fact that China typically describes children who are older or disabled due to physical needs as children with special needs. This designation rarely includes children with emotional or behavioral needs attributed to sexual abuse, drug exposure, violence, or substance use.24

The important point is that support services, informal and formal, should be available to all adoptive parents, regardless of whether the child is considered to have special needs. Close family and friends need to understand how important emotional and instrumental support is to new parents who have adopted a child. We know that such support is a buffer for those who experience depressive symptoms.

5. Do Not Let Stigma or Shame Prevent You from Seeking Help

For many adoptive parents, controlling events and situations is important, as is having a self-image of strength and competency. When we fall short of subtle expectations and begin to struggle, barriers to admitting that help is needed—barriers such as stigma, or an unwillingness to access help, caused by shame—may prevent parents from receiving the support they need. Sometimes, however, the parent reaches out to individuals who “don’t get adoption.” For example, when disclosures of emotional distress are made to well-intentioned family members, parents have reported being told, “Isn’t this what you wanted? You were so excited. What went wrong?” Remember, it is about parents expressing themselves without being judged, allowing them to admit how they are struggling, and reminding them that reliable estimates are that at least 12% of parents struggle with PAD. Overwhelmingly, we understand how important social support is to our mental well-being. There is a silent bond between adoptive parents—I have sensed it. A virtual support group or a partner’s support may be helpful so that the parent feels a sense of psychological safety, one of the most important factors in trauma-informed care.25 When an individual feels a sense of safety to share their struggles with others, healing can begin.

Assessing for PAD

As previously described, symptoms of depression follow the DSM-V criteria.26 However, parents may attempt to hide their emotions, especially out of fear that the adoption will be derailed or even disrupted. Parents have admitted these seem to be irrational fears; however, the pressure on adoptive parents is significant as they have to reach into society for a license to parent and thereby prove to others they are competent to raise a child. Feeling a sense of safety in sharing what they are feeling will benefit both the parent and child and avoid escalations of parental shame and guilt. Professionals need to approach parents in a compassionate way and ensure there are compassionate policies in their agencies for parents found to be struggling. Parents should understand these policies as conversations about PAD occur.

There are two general depression screening tools that may be used by parents as self-assessments and by professionals as part of their adoption process procedures: the Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale27 (CES-D) and the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9).28 The CES-D is a 20-item tool that asks about symptoms related to depression such as sleep quality, appetite, and loneliness. The PHQ-9, while shorter with 10 items (if you include the last item related to how difficult the symptoms make daily activities) also asks about the presence of depressive symptoms. One caveat is that they are based on self-reported items that screen for depressive symptoms. Although these tools are validated as instruments that pick up on depressive symptoms, they are merely screens, and the individual should be assessed by a mental health professional to verify the diagnosis of depression.

Conclusion

Despite June Bond’s groundbreaking work in 1995, we are still exploring the phenomenon of parental postadoption depression. We now have inklings, based on evidence, that PAD affects groups of parents across families and despite the heterogeneity of adoption. Yet using a framework based on parental expectations appears to be informative and even predictive, regardless of parents’ specific situations. Preparation and informative dialogues about PAD before adoption, peer and intimate family support, and a trauma-informed, adoption-competent mental health professional can be instrumental in helping parents who are struggling, and ultimately the children they are caring for. Parents who are experiencing depression deserve to feel psychologically safe, receive transparency to build trust with others, and receive nonjudgmental support.

Suggested Resources

- The Post-Adoption Blues: Overcoming the Unforeseen Challenges of Adoption — Dr. Karen J. Foli and Dr. John Thompson

- Middle Range Theory of Postadoption Depression — Dr. Karen J. Foli

- Adoption Advocate No. 78- The Post-Adoption Life: Supporting Adoptees, Birth Parents, and Families After Adoption — National Council for Adoption

- Postadoption Depression — Child Welfare Information Gateway

- Finding and Working with an Adoption-Competent Therapist — Child Welfare Information Gateway

- Find a Parent Support Group — North American Council on Adoptable Children (NACAC)

- Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs) Video — Center for Disease Control

- Myth: You and Your Adopted Child Will Feel Love at First Sight — Holt International

References

- Dean, C., Dean, N. R., White, A., & Liu, W. Z. (1995). An adoption study comparing the prevalence of psychiatric illness in women who have adoptive and natural children compared with women who have adoptive children only. Journal of Affective Disorders, 34(1), 55–60.

- Anthony, R. E., Paine, A. L., & Shelton, K. H. (2019). Depression and anxiety symptoms of British adoptive parents: A prospective four-wave longitudinal study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 16(24), 5053. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16245153; Foli, K. J., South, S. C., Lim, E., & Jarnecke, A. (2016). Post-adoption depression: Parental classes of depressive symptoms across time. Journal of Affective Disorders, 200, 293-302. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2016.01.049

- Goldberg, A. E., & Smith, J. Z. (2013). Predictors of psychological adjustment in early placed adopted children with lesbian, gay, and heterosexual parents. Journal of Family Psychology, 27(3), 431-442. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/a0032911; Pemberton, C. K., Neiderhiser, J. M., Leve, L. D., Natsuaki, M. N., Shaw, D. S., Reiss, D., & Ge, X. (2010). Influence of parental depressive symptoms on adopted toddler behaviors: An emerging developmental cascade of genetic and environmental effects. Development and Psychopathology, 22(4), 803–818. http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S0954579410000477; Tully, E. C., Iacono,W. G., & McGue, M. (2008). An adoption study of parental depression as an environmental liability for adolescent depression and childhood disruptive disorders. American Journal of Psychiatry, 165(9), 1148–1154.

- Liskola, K., Raaska, H., Lapinleimu, H., & Elovaino, M. (2018). Parental depressive symptoms as a risk factor for child depressive symptoms; testing the social mediators in internationally adopted children. European Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 27, 1585-1593. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-018-1154-8

- American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.books.9780890425596

- American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.books.9780890425596

- Nguyen, D. J., & Gunnar, M. (2014). Depressive symptoms in mothers of recently adopted post-institutionalized children. Adoption Quarterly, 17(4), 280-293. doi: 10.1080/10926755.2014.895464

- Senecky, Y., Hanoch, A., Inbar, D., Horesh, N., Diamond, G., Bergman, Y. S., & Apter, A. (2009). Post-adoption depression among adoptive mothers. Journal of Affective Disorders, 115, 62-68.

- Foli, K. J., South, S. C., Lim, E., & Jarnecke, A. (2016). Post-adoption depression: Parental classes of depressive symptoms across time. Journal of Affective Disorders, 200, 293-302. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2016.01.049

- Ibid.

- Beck, C.T. (2002). Revision of the Postpartum Depression Predictors Inventory. JOGNN, 31, 394-402

Beck, C.T., Records, K. & Rice, M. (2006). Further development of the Postpartum Depression Predictors Inventory-Revised. JOGNN, 35, 735-745. - Foli, K. J. (2010). Depression in adoptive parents: A model of understanding through grounded theory. Western Journal of Nursing Research, 32, 379-400. doi: 10.1177/0193945909351299

Foli, K. J., South, S. C., Lim, E., & Jarnecke, A. (2016). Post-adoption depression: Parental classes of depressive symptoms across time. Journal of Affective Disorders, 200, 293-302. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2016.01.049 (e.g., Foli,

Foli, K. J., Lim, E., & South, S. C. (2017). Longitudinal analyses of adoptive parents’ expectations and depressive symptoms. Research in Nursing and Health, 40(6), 564-574. doi: 10.1002/nur.21838 - Foli, K. J., Lim, E., & South, S. C. (2017). Longitudinal analyses of adoptive parents’ expectations and depressive symptoms. Research in Nursing and Health, 40(6), 564-574. doi: 10.1002/nur.21838

- Anthony, R. E., Paine, A. L., & Shelton, K. H. (2019). Depression and anxiety symptoms of British adoptive parents: A prospective four-wave longitudinal study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 16(24), 5053. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16245153

- Foli, K.J., South, S.C., Lim, E. (2012). Rates and predictors of depression in adoptive

mothers: Moving toward theory. Advances in Nursing Science, 35(1), 51–63. http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/ANS.0b013e318244553e - Foli, K. J. South, S. C., Lim, E., & Hebdon, M. (2013). Depression in adoptive fathers: An exploratory mixed methods study. Psychology of Men & Masculinity, 14(4), 411-422. doi: 10.1037/a0030482 ).

Liskola, K., Raaska, H., Lapinleimu, H., & Elovaino, M. (2018). Parental depressive symptoms as a risk factor for child depressive symptoms; testing the social mediators in internationally adopted children. European Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 27, 1585-1593. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-018-1154-8 - Foli, K. J. South, S. C., Lim, E., & Hebdon, M. (2013). Depression in adoptive fathers: An exploratory mixed methods study. Psychology of Men & Masculinity, 14(4), 411-422. doi: 10.1037/a0030482

- Child Welfare Information Gateway. (2019). The impact of adoption. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Administration for Children and Families, Children's Bureau. https://www.childwelfare.gov/pubPDFs/factsheets_families_adoptionimpact.pdf

- Ibid.

- (Felitti, V. J., Anda, R. F., Nordenberg, D., Williamson, D. F., Spitz, A. M., Edwards, V, Koss, M. P., & Marks, J. S. (1998). Relationship of childhood abuse and household dysfunction to many of the leading causes of death in adults: The Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) study. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 14(4), 245-258.

Merrick, M. T., Ford, D. C., Ports, K. A., & Guinn, A. S. (2018). Prevalence of adverse childhood experiences from the 2011–2014 behavioral risk factor surveillance system in 23 states. JAMA Pediatrics, Published online September 17, 2018. doi:10.1001/jamapediatrics.2018.2537 - Foli, K. J. (2010). Depression in adoptive parents: A model of understanding through grounded theory. Western Journal of Nursing Research, 32, 379-400. doi: 10.1177/0193945909351299; Foli, K. J., South, S. C., & Lim, E. (2014). Maternal postadoption depression: Theory refinement through qualitative content analysis. Journal of Research in Nursing, 19(4), 303-327. doi: 10.1177/1744987112452183

- Martin, N. G., & Rosenhauer, A. M. (2016). Psychological functioning through the first six months in mothers adopting from China: Special needs versus non-special needs. Adoption Quarterly, 19(4), 261-283. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/10926755.2015.1121186

- Ibid.

- Martin, N. G., & Rosenhauer, A. M. (2016). Psychological functioning through the first six months in mothers adopting from China: Special needs versus non-special needs. Adoption Quarterly, 19(4), 261-283. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/10926755.2015.1121186

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA). (2014). SAMHSA’s concept of trauma and guidance for a trauma-informed approach. HHS Publication No. (SMA) 14-4884. Rockville, MD. https://ncsacw.samhsa.gov/userfiles/files/SAMHSA_Trauma.pdf

- American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.books.9780890425596

- Radloff, L.S., 1977. The CES-D scale: a self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Appl. Psychol. Meas. 1 (3), 385–401.

- Kroenke, K., Spitzer, R. L., & Williams, J. B. (2001). The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 16(9), 606–613.

Originally published in 2021 by National Council For Adoption. Reprinting or republishing without express written permission is prohibited.