The Multiethnic Placement Act (MEPA): Analysis and Trends After 25 Years

Adoption Advocate No. 162

Renewed discussion of racial inequality throughout the U.S. has revitalized attention to racial disproportionalities in the child welfare system and how they might best be addressed. The Multiethnic Placement Act (MEPA) sits at the heart of this discussion. This month’s issue of the Adoption Advocate reviews a recent study of the implementation of MEPA and its findings, including significant progress in reducing racial disproportionality and substantial differences among states’ implementation of diligent recruitment plans.

Finding adoptive families that ensure long-term connections and support for children in foster care who cannot return to their biological families has been a longstanding goal in the child welfare field. The Multiethnic Placement Act (MEPA) of 1994, as amended by the Interethnic Adoption Provisions of the Small Business Job Protection Act of 1996, was intended to reduce the time children spent in foster care awaiting adoption. At the time, Black children and some other racial groups were overrepresented in foster care and spent more time in foster care compared to other groups. Some advocates believed that there was discrimination in the placement process and that efforts to place children with adoptive families of the same race and cultural backgrounds were delaying and denying family opportunities for those children and potential parents of different backgrounds. The two laws tried to clarify the role that race and background should play in placement decisions. The laws affected child welfare policy by:

- Prohibiting state child welfare agencies from refusing or delaying foster or adoptive placements because of a child’s or foster/adoptive parent’s race, color, or national origin;

- Prohibiting state child welfare agencies from considering race, color, or national origin as a basis for denying approval of a potential foster or adoptive parent;

- Requiring state child welfare agencies to act diligently to recruit a diverse group of foster and adoptive parents who reflect the racial and ethnic makeup of children in out-of-home care.

Concern about these issues remains relevant more than 25 years later as child welfare agencies try to balance the dual goals of supporting the healthy development of children’s racial and cultural identities and assuring their rapid placement with a loving family. Further, today the field understands more about how disparities on the front end of the system – in adverse circumstances, maltreatment reports, investigations, substantiations, and foster care placements – influence which children come into foster care, how much time they spend in care, their likelihood of reunification, and whether children experience termination of parental rights and are placed with adoptive families. Race plays a role at each stage of the child welfare system, and we are still struggling as a field with how to address these issues in ways that maximize children’s interests.

In response to an Executive Order issued in June 2020 titled Strengthening the Child Welfare System for America's Children, the Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation within the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services conducted a study of the implementation of the MEPA requirements. This article describes the study and its major findings. For those interested in the full study, a series of written products may be found here: https://aspe.hhs.gov/reports/multiethnic-placement-act-transracial-adoption-25-years-later.

The study included three components:

- Analysis of trends in adoption and transracial adoption based on data from the federal Adoption and Foster Care Analysis and Reporting System (AFCARS) which contains annual data on every child in foster care in the United States;

- Content analysis of the Diligent Recruitment Plans each state submits to the Children’s Bureau every five years as part of their state plan documenting how they spend money from federal child welfare programs;

- Interviews with state adoption officials and stakeholders in three states – Arizona, Oklahoma, and Oregon – about their implementation of MEPA and their current experience with its requirements.

This study did not focus on adoption trends for American Indian children because many adoptions of American Indian children fall under the authority of the Indian Child Welfare Act, the requirements of which are quite different from those under MEPA, making direct comparisons misleading.

Trends in Adoption Generally and Transracial Adoption Specifically

Context on Disproportionality and Disparity. As in many other fields, central to discussions about race in the child welfare system are the concepts of disproportionality and disparity. Disproportionality refers to the overrepresentation or underrepresentation of a racial or ethnic group compared to its percentage of the total population, while disparities refer to differential outcomes by race or ethnicity. In the U.S. child population overall (ages 0 to 18), 50 percent are non-Hispanic White, 26 percent are Hispanic, 14 percent are non-Hispanic Black, 5 percent are Asian, 4 percent are multiracial, and 1 percent are American Indian or Alaska Native. These figures are provided as context for the statistics on foster care and adoption presented below. In the figures below, Hispanic children regardless of race are referred to as Hispanic, and the Black and White categories include non-Hispanic persons in those racial groups. Within the child welfare system overall, White and Asian children are consistently underrepresented, while Black children are consistently overrepresented. American Indian children are usually overrepresented except in some data on maltreatment reports. Statistics for Hispanic children are more complex and vary depending on the topic.

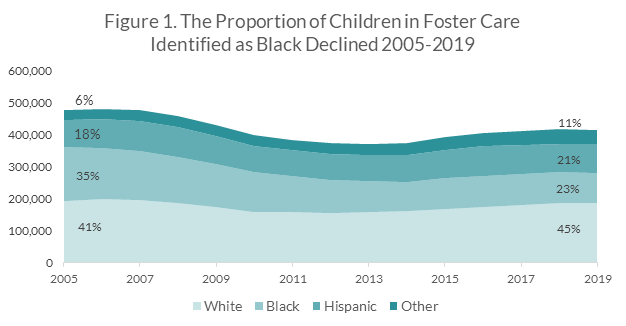

The number of children in foster care declined. Our study examined data on foster care entries and exits in three-year groupings, beginning with 2005-07 and ending with 2017-19. During this period, the number of children in foster care declined by 14 percent, due both to declining numbers of foster care entries and higher rates of foster care exits. As shown in Figure 1, declines in the foster care population were more pronounced among Black children than for White or Hispanic children. The number of children in foster care affects the number of children potentially available for adoption.

More adoptions and fewer reunifications, especially for White and Hispanic children. Since 2005-07, both the number and proportion of children exiting to adoptions and guardianships each increased, while the number and proportion of children reunified with a parent or caretaker and exiting to a relative without guardianship both decreased. These changes were much more pronounced in the White and Hispanic populations than among Black children. Increases in the number of adoptions occurred primarily among White children (+41 percent) and Hispanic children (+36 percent), while the number of adoptions of Black children decreased substantially (-22 percent), in part because of decreasing numbers of Black children in foster care.

Higher proportion of transracial adoptions, especially of Black children. As shown in Table 1, the proportion of transracial adoptions also increased during this time span, primarily for Black children. Transracial adoptions increased from 23 percent to 28 percent of all adoptions overall and from 21 percent to 33 percent for Black children. Transracial adoptions of Hispanic children declined from 49 percent to 46 percent. Transracial adoptions of White children remained quite rare but increased from 4 percent to 6 percent. Overall, 90 percent of transracial adoptions involved children of color adopted by parents of a different race.

Table 1. The Vast Majority of Transracial Adoptions Involve Children of Color |

||||||

| Percent of Adoptions That Were Transracial | ||||||

| 2005-2007 | 2017-2019 | |||||

| Adoptions of Black Children | 21% | 33% | ||||

| Adoptions of Hispanic Children | 49% | 46% | ||||

| Adoptions of White Children | 4% | 6% | ||||

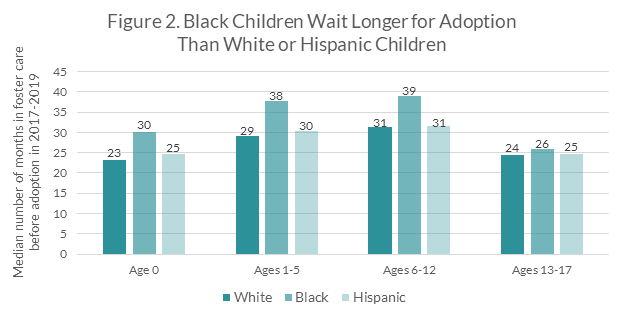

Disproportionality has eased somewhat, but Black children continue to remain in foster care longer before being adopted. As foster care populations declined through most of the years we looked at, the disproportional representation of Black children in foster care nationally eased somewhat. Between 2005-07 and 2017-19, the proportion of children in foster care who were identified as Black declined from 35 percent to 23 percent, while the proportion identified as White increased from 41 percent to 45 percent and those identified as Hispanic increased from 18 percent to 21 percent. Children of other races or multiracial increased from 6 percent to 11 percent. However, a child’s race remains associated with time spent in care prior to adoption. Black children adopted between 2017 and 2019 spent the longest time in foster care prior to adoption, with a median of 33 months in care before adoption, compared to a median of 27 months for White children and 28 months for Hispanic children. As shown in Figure 2, Black children spend longer in care prior to adoption than do White or Hispanic children in all age groups, though the difference was much lower among youth ages 13-17.

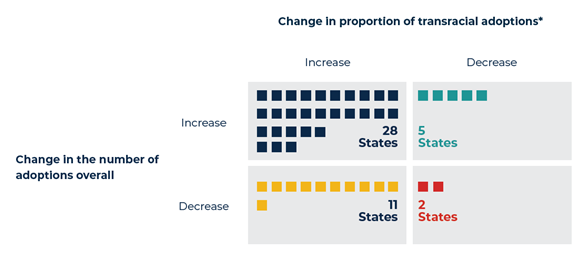

Similar trends in most states. While there were differences among states, 28 states saw increases in both the number of adoptions overall and the proportion of those adoptions that were transracial. In just seven states the proportion of transracial adoptions decreased, five of those in the context of increased adoptions and two in the context of decreased adoptions. There were 13 states in which adoptions decreased overall during this period; in 11 of those the proportion of transracial adoptions increased nonetheless. These statistics are shown graphically in Figure 3.

Figure 3. Most States (and the District of Columbia) Increased the Proportion of Transracial Adoptions and the Number of Adoptions Overall

* New York, Maine, Massachusetts, West Virginia, and Washington are not included given insufficient race/ethnicity data across time periods.

Strengths and Weaknesses in States’ Diligent Recruitment Plans

Diligent Recruitment Plans (DRPs) are intended to ensure that states seek foster and adoptive families reflecting the characteristics of children who need care. Federal guidance directs states to include these eight components in their plans:

- A description of the characteristics of children in foster care needing adoptive families;

- Specific strategies to reach all parts of the community;

- Diverse methods of disseminating both general and child-specific information;

- Strategies for assuring that all prospective parents have access to the home study process;

- Strategies for training staff to work with diverse cultural, racial, and economic communities;

- Strategies for dealing with linguistic barriers;

- Non-discriminatory fee structures;

- Procedures for ensuring a timely search for prospective parents awaiting a child.

The federal monitoring process known as the Child and Family Services Reviews (CFSRs) includes an assessment of the adequacy of each state’s DRP. We reviewed states’ ratings on this item in the most recent round of CFSRs which were conducted between 2015 and 2018. In addition, we reviewed the content of states’ DRPs which are a component of their larger Child and Family Services Plans that currently cover the five-year period from 2020 through 2024.

Sixteen states received a “strength” rating on the item in the CFSR relating to diligent recruitment and 34 states received a rating of “area needing improvement.” For the states rated as needing improvement, common issues included little monitoring or oversight taking place between states and counties and a lack of sufficient data systems in some counties to track race and ethnicity of potential adoptive parents. For instance, some states did not have systems set up to track race/ethnicity data, had poor quality systems, or had not trained staff to use the system effectively. Additionally, many states noted that the pool of foster parents was too small and they found it difficult to retain existing foster parents. Many of the states either did not assess changes in their racial and ethnic demographics or did not have a systematic process in place to review and monitor data. In addition, some states that collected the relevant data did not describe how they used it to improve recruitment efforts. Moreover, some states did not have the capacity to meet the language needs of foster children, particularly for Spanish-speaking children. Finally, some states decentralized recruitment efforts, making local departments responsible for finding resource families. In these cases, recruitment efforts could vary greatly throughout the state, making the statewide plan less cohesive.

Our review of the content of DRPs found that three states included very sparse information which included few of the expected elements. Among the remaining states, the information most likely to be missing included:

- Strategies for ensuring that all prospective parents have access to the home study process

- Strategies for training staff to work with diverse cultural, racial, and economic communities

- Strategies for dealing with linguistic barriers

- Nondiscriminatory fee structures

Each of these elements was missing from between 13 and 17 states’ plans. While the efforts described in states’ DRPs vary, several themes emerged.

Nearly all states described characteristics of children waiting to be adopted. Demographics in most plans included children’s race, ethnicity, age, and gender. Some states also provided information on the number of children with special needs. Some states described how they used this information to seek adoptive families suited to meet the needs of waiting children.

Many states described outreach efforts to reach diverse communities. Some plans included maps or reported needs by region. Others described networking with community partners including religious organizations and grassroots groups. Some partnered with media outlets or used social media to reach underrepresented populations. And many participated in a range of events and festivals popular with populations they were trying to reach. For instance, some states highlighted trying to reach families of particular racial or ethnic groups through community festivals while others sought LGBTQ+ families at Pride events. Hotlines, media outreach, and participation in local events were all used by multiple states. Through these efforts and others, such as websites, states sought to ensure that people knew how to inquire about becoming a foster parent.

Child-specific recruitment efforts are critical. States increasingly rely on child-specific recruitment strategies and forming partnerships to advance this work. Forty-three states mentioned child-specific efforts including Wendy’s Wonderful Kids, the Heart Gallery, Wednesday’s Child, AdoptUSKids, and the Adoption Resource network (see sidebar).

Training helps staff work effectively with diverse cultural, racial, and economic communities. States used both preservice and in-service training on working with diverse populations. Common training topics included cultural sensitivity and competency, implicit bias, and working with families that vary in socioeconomic status and/or sexuality.

States have developed strategies for dealing with linguistic barriers. Among the most common approaches to addressing linguistic barriers are translators and/or translation and interpretation services. Many states translated documents and recruitment materials into Spanish and advertised on Spanish language radio. Some states also offered services in other languages depending on local needs. These languages included Hmong, Russian, Somali, and Vietnamese. Some states also made sign language interpreters available as needed.

Retention is critical to ensuring a sufficient supply of foster and adoptive families. Diligent recruitment efforts in many states included improving the retention of existing foster parents. For example, States did this by highlighting the positive work of foster parents in newsletters, conducting surveys to assess foster parent satisfaction, offering ongoing training and support for foster parents, and offering mentors to foster and adoptive parents, including after adoption. Retention efforts are key to maintaining enough licensed foster parents for children in many states.

Perspectives of Adoption Officials and Stakeholders in Three States

Interviews with state adoption officials and stakeholders were intended to gain insights into how staff implement the MEPA requirements. In selecting states for the interviews, we sought a small sample of states that differed by geography, size, and some key adoption indicators. Officials in Arizona, Oklahoma, and Oregon agreed to speak with the study team about their practices. The findings described below reflect the experiences of these states but may not represent the practices and circumstances in other states.

Between six and eight individuals were interviewed in each state, in a combination of individual and small group interviews, all held virtually. Interview guides included questions about how states recruit foster parents from diverse backgrounds, how they support adoption matches, how they determine which families are considered for adoption matches, whether or how race is considered in placement decisions, and the practices they have in place to prevent discrimination based on race, color, or national origin.

Although Arizona and Oklahoma have both seen dramatic increases in adoptions over the past two decades, Oregon was one of only a few states that saw a decrease in the rates of both adoption and transracial adoption. Children in Oregon also appeared to wait in care longer than they did in most other states.

The vast majority of children adopted from foster care are adopted by their foster parents or relatives. State officials reported that most children were adopted by someone already associated with the child. AFCARS data for 2019 confirm that 88 percent of children adopted from foster care that year were adopted by either their foster parents (52 percent) or relatives (36 percent). States emphasized the importance of and focus on leveraging children’s existing connections for finding foster and adoptive parents, and prioritized child-focused recruitment for locating adoptive families for waiting children without prospective adoptive parents. But while over half of children adopted from foster care were adopted by foster parents, the initial matching of children with foster parents was far less systematic than the carefully consider adoption matching processes described by states for children without identified adoption resources.

States rely heavily on data to assess the need for foster and adoptive caregivers. States reported categorizing the need for resource families by children’s demographic characteristics, including race. Each of the states used “recruitment estimators” or similar data management systems that helped to track progress toward recruitment targets. States then used targeted marketing campaigns to help increase the number of foster and adoptive families for children who were harder to place, such as adolescents and children of color. Staff in Arizona described efforts to close inactive foster home licenses to get a more accurate count of new resource families needed. Oklahoma regularly used data on the race and age of children in need of care to focus its recruitment strategies. Geographically focused strategies were described in both Arizona and Oklahoma as part of efforts to keep children near their communities and social networks.

Partnerships and marketing efforts are important tools for recruiting foster and adoptive families. States partnered with private, community-based, and religious groups to connect with a broad range of foster and adoptive families. Often these partnerships focused on a particular racial or ethnic group or community underrepresented in the agency’s existing resource pool as compared with the children in care. Oklahoma worked with One Church One Child to conduct general recruitment and with The Heart Gallery for child-focused recruitment. All three states also worked with Wendy’s Wonderful Kids and with a range of adoption websites. Marketing campaigns similarly used market segmentation to boost foster parent licensing among underrepresented groups. Strategies included mailers, postcards, and refer-a-friend campaigns, as well as using social media and outreach at community events.

Supporting and retaining foster parents is key to maintaining an adequate and diverse supply of homes. In addition to recruitment efforts, states realized that minimizing the loss of current resource families eased their constant cycles of catching up from shortages. Examples included “foster parent retention champions” in Oregon who provided leadership on how to work with specific populations. In Arizona, surveys of current foster families were used to seek information about their experiences and needs. This information was in turn used to provide training and supports in areas of identified need.

States reported that a range of factors go into identifying adoptive families for particular children. Even when children indicated a preference for a family of a particular race, states prioritized other foster parent characteristics (such as ability to meet a child’s special needs or interest in adopting a teenager). All states noted that race was never a deciding factor in matching and placement, and that they considered many factors when placing children in adoptive families.

States reported efforts to prevent discrimination based on race, color, or national origin. All three states trained staff in the MEPA law. When asked about how they avoided discrimination based on race, a common response was to describe how staff were trained to understand “cultural” needs of children in transracial adoptions rather than race or ethnicity, and to offer training to foster parents to help them attend to children’s cultural and ethnic needs.

Adoption is viewed within the context of other permanency indicators. During interviews, some states discussed their adoption efforts in the context of other permanency efforts. It is important to note that the extent to which some states were focused on improving adoption rates could be related to how they prioritized other permanency goals, particularly reunification, as well as prevention of foster care placements.

Key Takeaways

The three components of this research – quantitative analysis of AFCARS data, content analysis of states’ Diligent Recruitment Plans, and interviews with key informants in three states – provide a range of information about how adoption practice and outcomes have evolved in the years since MEPA was initially implemented and the current issues in adoption practice that relate to the race, color, and national origin of children and resource families. The issue of how children’s race, color, and national origin are or should be considered in foster care and adoptive placements remains relevant and has become more fraught as the child welfare system reconsiders the way family separations – temporary and permanent – are entwined with issues of racial inequities.

In the years since MEPA and its amendments were enacted, the number and proportion of transracial adoptions from foster care have increased substantially, with the vast majority of transracial adoptions involving children of color adopted by White families. In addition, years of effort on the part of many within the child welfare system have resulted in somewhat reduced racial disparities in adoption, though substantial disparities remain. The number of Black children in and adopted from foster care annually has declined substantially, while the number of White and Hispanic children adopted has grown. The gaps in wait times before adoption are smaller than in the past and the likelihood of adoption versus reunification are more similar between racial and ethnic groups than they once were. However, Black and American Indian children still wait longer than children of other races for adoption. Gaps are not as large for Hispanic or Asian children.

States make a variety of efforts to recruit diverse foster and adoptive parents. However, the quality of Diligent Recruitment Plans varies widely. And while many states’ plans aim to be data driven, there are challenges to the availability and quality of data—particularly with respect to recruitment—that make it difficult to judge the success of intended recruitment efforts. Because most children are adopted either by their foster parents or by someone in their extended birth family or social networks, ensuring a diverse population of foster parents is especially important. Additional attention is needed to ensure matches with foster parents are as carefully considered and purposeful as adoption matches so that the full range of children’s needs are met.

Key informant interviews revealed that there is still confusion in the field about what is and is not allowable in taking race into account in adoption decisions, and there is some conflation of race and culture in this process. Renewed discussion of racial inequality throughout the U.S. has revitalized attention to racial disproportionalities in the child welfare system and how they might best be addressed. Child welfare agencies across the nation, along with the families they serve and advocates working from many perspectives, are engaging in reinvigorated debates about MEPA and its implications for children and families and the agencies that serve them.

This article is adapted from research conducted by Mathematica under contract to the Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation within the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. The views expressed here are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect positions of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

Originally published in 2021 by National Council For Adoption. Reprinting or republishing without express written permission is prohibited.

Watch the video conversation with co-author Laura Radel and NCFA's Ryan Hanlon as they breakdown the big takeaways from this study and answer frequently asked questions about MEPA.

About the Authors

Laura Radel is a Senior Social Science Analyst in the Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). ASPE operates as an in-house think tank within the Office of the Secretary of HHS, using research and policy analysis to consider ways of improving HHS programs and policies. Ms. Radel has worked in ASPE’s Division of Children and Youth Policy since 1989 and is a subject matter expert in federal child welfare programs and policy issues. In addition to overseeing the study discussed here on the Multiethnic Placement Act, her recent projects have included the Title IV-E Prevention Services Planning Toolkit, a study looking at exceptions states make to the ASFA termination of parental rights timeline, and a series of reports exploring the relationship between substance use and foster care entries.

Allon Kalisher is a hands-on expert in child welfare programs, policies, and data. He has more than 20 years of experience working in a state child welfare system, from the frontline to senior leadership roles in operations and strategic, analytic, and quality improvement. Kalisher, who joined Mathematica in 2019, has supported several projects and emerging partnerships to advance work in child welfare focused on data quality, predictive analytics, data linking, data analysis training, FFPSA implementation, and program evaluation and planning.

Kalisher came to Mathematica from the Connecticut Department of Children and Families (DCF), where he served as the Child and Family Services Review Program Improvement Plan manager, and from New Zealand’s Centre for Social Data Analytics, where he consulted on the implementation of the Douglas County Decision Aide (a predictive risk model designed to support call-screening decisions) developed for Douglas County, Colorado. Before that, he was a regional administrator, overseeing field operations and contract agencies for the Connecticut DCF’s Region 3. He started his career in child welfare as a frontline social worker and later led projects to build child welfare workforce capacity to use data, to improve the quality of federal data submissions, and numerous analyses to support performance evaluation and strategic planning.