Third culture kids: what is your child experiencing?

Introduction–What is a Third Culture Kid?

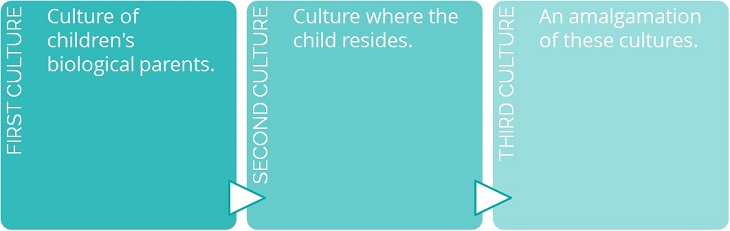

Third culture kid (TCK) refers to children raised in a culture outside of their biological culture for a significant part of their developmental years.1

Sociologist Ruth Hill Useem coined the term "Third Culture Kids" in the 1950s when watching her children inherit part of the culture of India during her research there. Initially, "third culture" referred to the process of learning to relate to another culture, but as sociology and research developed, TCK began to refer to children who accompany their parents into a different culture.2

Ruth Van Reken, author of Third Culture Kids: Growing Up Among Worlds, comments that while a TCK “builds relationships to all the cultures, [he does] not having full ownership in any. Although elements from each culture are assimilated into the third culture kid’s life experience, the sense of belonging is in relationship to others of the same background, other TCKs.”3 Third culture kids can be missionaries’ children, army “brats,” foreign service families, or business kids that move internationally on their parents’ schedules. TCKs have different characteristics and impacts than their peers of the same age group who are single-culture kids; some of the statistics can be found here.

How does being a Third Culture Kid relate to adoption?

Adopted children often learn their birth culture through a secondary means. For example, a child born in China (first culture), raised in America (second culture), and learns about China (third culture) has a unique set of challenges inherent to cultural understanding. Anthropologically speaking, humans learn culture through enculturation; i.e. comprehending nuances, expressions, language, gestures, and interactions through immersion. A child learns sarcasm as his or her brain develops to understand there are multiple (sometimes humorous) meanings to a phrase. However, adopted children learning about their birth cultures are much like anthropologists, and learn, at least in part, through being taught via acculturation, as an outsider.

Sometimes TCKs who are adopted don’t match the strict profile of “moving around constantly” and “growing up overseas.” Therefore, a subset definition has been created for them called Cross-Cultural Kids (CCK). A CCK “is a person who has lived in—or meaningfully interacted with—two or more cultural environments for a significant period of time during developmental years.”4 Adoption, especially internationally or transracially, can create challenges that aren’t found in families of a single background. On the one hand, adoption in America contributes toward a growing trend of multiracial and multiethnic families. On the other, “[r]esearch suggests that same-race and transracially adopted children begin to become aware of racial differences, as well as their adoptive status, as early as 4–5 years of age.”5

As transracial adoptees become adults, they further recognize the differences, and “experience feelings of loss of birth culture and family history and the growing awareness of racism and discrimination in their everyday lives.”6 Adoptive parents, “most of whom are White and of European descent, likewise are confronted with decisions about when and how to appropriately acknowledge and address ethnic and racial differences [and]… decide whether they want the children’s birth culture to be a part of the family’s life experiences and, if so, to what extent.”7 Too often while racial diversity is recognized by parents and communities, but cultural diversity is not.8

TCKs and CCKs can often feel a sense of “non-belonging” and in learning about a culture from the outside, suffer from Imposter Syndrome (e.g. “I’m not really this ethnicity, I’m a fraud;” “I can’t be accepted as being from this country or another”). For adopted children, must confront that learning a culture is not “as inherent or natural a process as it is for same-race or same-ethnicity families, and transracial adoptive parents must make a clear and explicit effort at cultural socialization.”9 This clear and explicit effort to incorporate culture can be one of the hesitations parents have about adopting transracially.

What then, is an adoptive parent to do?

Working hard at bringing a child to their birth culture is much like leading a horse to water; you can introduce the arts, food, music, language, and camps, but you can’t make children love their birth culture unless they want to. Younger children are more likely to engage in cultural socialization practices, “because younger children generally are more receptive to these activities and opportunities and there are greater post-adoption resources available to families who adopted more recently”. Older children may be less interested in cultural experiences than in peer acceptance.10 This usually swings back around when adoptees become young adults and are more interested in actively pursue acculturation themselves.

In the end, there is no denying that a CCK will never be “truly” their birth culture. It’s time to tell them the truth: that’s okay. The world is changing into a multi-ethnic, diverse place, full of people who immigrate and emigrate, marry cross-culturally, and have children of mixed cultures and races. While an adopted child may not feel belonging in a single culture, but they do belong in a new one: TCK and CCK. Cross cultural communities and knowledge that there are others like them can be extremely beneficial to transracially adopted children. While this may not be on the radar for your child now, cliché as it is, it won’t be an issue “until it is.”

Introducing third culture kids to others like them will bring them comfort – whether or not they realize it. Though the world is becoming more multi-ethnic, multi-racial, and diverse, it is still developing, and being the forerunners and pioneers into a changing society can feel very slow and lonely in real time. Learning about a culture second-hand is difficult, but not impossible. TCKs bring new experiences, views, and interests to established cultures, and have achieved notable success in creating “new jobs” and “new fields” by seeing a need overlooked by a certain society as “the way it is.”

Your child should not view themselves as falling through the cracks of two separate cultures, but rather the seedling in creating a new culture entirely, composited of the positive experience you have given her, and the type of cross-cultural love you have already demonstrated in creating a multi-racial, multi-ethnic family. At the end of the day, the person your child will learn from most is you.

Additional Reading

- http://denizenmag.com/third-culture-kid/

- http://denizenmag.com/2011/07/showing-sophie-her-cultural-heritage/

- http://www.brainchildmag.com/2013/06/adopted-childrens-cultural-identity/

Sources

- (Third Culture Kid).

- (Third Culture Kids Community, 2008).

- (Useem).

- (Jones, 2013).

- (Brodzinsky, Singer, & Braff, 1984; Huh & Reid, 2000).

- (Meier, 1999; Powell & Affi, 2005)

- (Friedlander, 1999).

- (Reken, 2009).

- J Fam Psychol. 2006 Dec; 20(4): 571–580.

- (Steinberg & Hall, 2000).