Adoption Agencies Serving Children in Foster Care

Adoption Advocate No. 95

Introduction

Historically, private adoption agencies were founded to work on domestic infant and international adoptions. As time has passed and new policies and best practices have been established, the face of adoption continues to change, and the availability of infants for domestic and international adoption has steadily declined. Today, adoption costs for families continue to climb, and the wait can stretch for years.

Just as adoption has changed over time, so too have the agencies providing adoption services. In recent years, EVOLVE and many other agencies have adjusted their international adoption programming to focus on the adoption of older children and subsequently provide training to adoptive parents, looking for new and better ways to provide ethical, child-focused services that will support families over the long term. Many of the services we’ve expanded in recent years can also be adapted to serve foster youth in our own communities who are awaiting families through adoption.

We must consider the truth that there are also thousands of children living in our own communities, waiting to be adopted out of foster care. Child-focused private adoption agencies can work to expand our missions and evolve in order to help find permanent, loving homes within our communities for the children who already live here – children who have been separated from their original families due to no fault of their own and still await a permanent place to call home.

By the Numbers

In 2008, 135,813 children were adopted in the U.S. via all types of adoption: adoption from foster care, intercountry adoption, and domestic infant adoption. Two-fifths of these adoptions occurred through public child welfare agencies. Although the trend has become obvious – that is, that adoptions through the foster care system are increasing and international adoptions are decreasing – many private adoption agencies have not incorporated local adoption through foster care into their programming, or have only done so recently.1

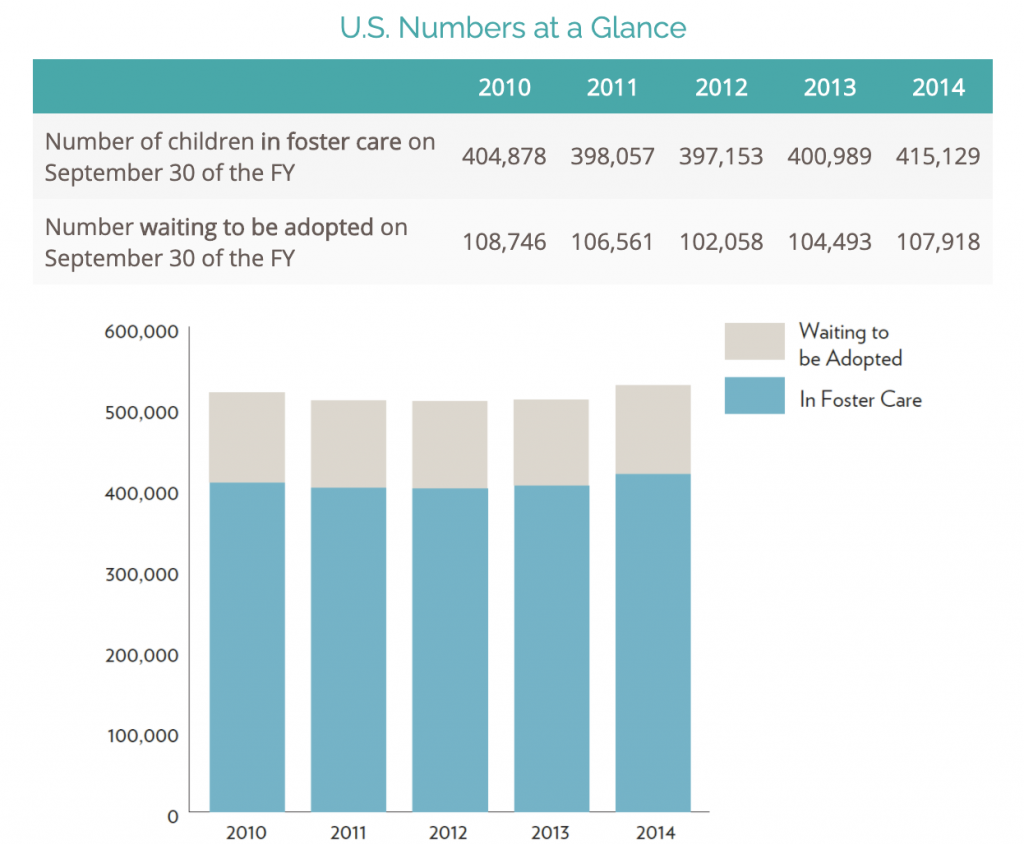

We know that only about half as many children are adopted each year (50,644 in 2014)2 from foster care as remain waiting to be adopted. There is much work still to be done for the children waiting in our own backyards, and private agencies – with their dual expertise in recruiting prospective adoptive families and providing professional support services to families that have adopted – can play an important role in helping children find the permanence that research and anecdotal experiences tell us they need.

Last year, more than six million U.S. children were involved in reports of abuse or neglect. More than 400,000 entered foster care, the second consecutive annual increase in the number of children entering care after many years of declining numbers – a highly alarming trend. Of the over 400,000 children in the U.S. foster care system, nearly 108,000 are currently available for adoption.

Source: The AFCARS Report, Preliminary FY 2014 Estimates as of July 2015, retrieved online at: http://www.acf.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/cb/afcarsreport22.pdf

Programming Opportunities

Although the ultimate responsibility for children in foster care rests with the state, private agencies can be valuable partners in supporting permanency for children in the foster care system. Private agencies providing foster care services can offer expertise and multiple supports, which can lead to an increased number of successful and stable adoptions when efforts to reunite families are not successful. More and more agencies are branching out, sometimes in partnership with state governments and agencies, to better serve youth in care as well as the larger community by expanding traditional foster care services.

Private agency foster care programs can address various needs for children and communities. In Minnesota, 18 agencies currently provide four primary types of family based foster care programs:

- Emergency Shelter Foster Care: Provides short-term foster care (typically up to 45 days) for children who are in immediate need of a home.

- Standard Foster Care: Provides longer-term (beyond 45 days) care to children whose parents may or may not have had their parental rights terminated.

- Intensive Foster Care: Often used as a transition from or alternative to more restrictive programs, including residential treatment centers or hospitals. Intensive foster parents are part of a treatment team of social workers, therapists, and other professionals designed to help children and families meet their goals.

- Treatment Foster Care: Often the children in care in these homes have a higher need than what can be addressed in a standard foster care home, but may not have had formal treatment or hospitalizations. Foster parents are part of a treatment team of social workers, therapists and other professionals designed to help children and families meet their goals.

Within these four types of foster care programs, families are able to choose to become a traditional or concurrent foster care home. A traditional home means that families volunteer for the purpose of providing temporary foster care. A concurrent home is one where a family is trained and commits to supporting a child’s reunification, helping to maintain social and emotional connections with their families. At the same time, concurrent families are willing to adopt these children if reunification is not successful. Concurrent homes can help ensure there are fewer traumatic removals and difficult adjustments for children.

EVOLVE’s services are child-focused, meaning that all of our program planning and implementation is initiated with the best interest of children being the first and foremost goal. We have found that if children cannot remain in the biological parent’s home, finding permanency with another family, without multiple disruptions, is in their best interests. This is why our programs encourage timely reunification with biological parents whenever possible, and adoption with a qualified family when reunification is not an option.

However, the policies impacting financial support for foster care versus adoption often encourage the practice of children growing up in the foster care system. This causes the negative impact of aging out, leaving many without the skills and support they need to make it on their own.3 Only 58 percent of youth who age out of foster care will graduate from high school by 19, and only 3 percent will graduate from college by age 25. One in four will be involved in the justice system within 2 years. Only half of aged out youth are employed at age 24. Seventy-one percent of young women who age out of foster care have experienced pregnancy by 21, and more than one in five will face homelessness.4 Aging out of care often has a lasting negative impact on a former foster youth’s life, and also represents a cost to our communities. The economic cost of foster care is approximately $13.5 billion annually, and additional costs to the state are often incurred once children age out of the system and too many find themselves incarcerated, homeless, unemployed, or pregnant before becoming financially independent.5

When neglect, abuse, and a high number of caretaking environmental changes are present, the negative impact on children is significant. This impact tends to escalate as the child’s age at placement increases. Connecting children to family before they are allowed to “age out” of care must be a national priority, and research shows that even providing financial assistance to families that adopt waiting children and to the agencies supporting and serving those families can prove an excellent return on investment for communities.6

Children thrive in environments that include an invested adult who they can depend upon and connect with, and families are strengthened through continued targeted services provided by agencies ready to support their ongoing needs. With these supports in place, the negative outcomes reported for children leaving foster care without a family can be significantly reduced.

At EVOLVE, our foster care services began primarily as a standard program with both traditional and concurrent options. We focus on small caseloads with intensive case management for both families and children to maintain stable, successful placements. Initially, we projected that most families would choose to provide traditional homes verses concurrent (80% traditional versus 20% concurrent). In the two years since this program has been fully implemented, most families entered on the traditional path but soon changed to concurrent, eventually adopting the children in their care. Last year alone, 60% of our families finalized an adoption.

Additional support services available to youth and families involved in the foster care system include:

- Child-Focused Recruitment: Recruiters focus on individual children who are waiting in the system for an adoption. The worker focuses on building a relationship with the child, preparing them for adoption, and searches intensively for family/kin, neighbors, associations, or interested families who could provide a permanent home.7

- Therapeutic Supervised Visitation: This program has the goal of reuniting families in the child welfare system and assisting them in learning and developing more positive, effective parenting skills and expectations for healthy familial relationships.

- Trauma-Informed Family and Individual Counseling: Provides mental health services with a thorough understanding of the profound neurological, biological, psychological, and social effects of trauma and violence on an individual. Often agencies employ therapists who are also adoption competent, benefiting families and adoption programming.8

- Independent Living Skills: Provides life skills training to youth aging out of the foster care system to assist in the transition to a successful, independent lifestyle.9

Several agencies have increased their efforts to serve the needs of their communities by providing flexible services supporting both family reunification and fostering/adoption. When reunification is not possible, we must be ready to help children find permanent, nurturing homes with minimal disruptions in their lives and in a timely manner. This challenging mission can be both heart-wrenching and extremely rewarding.

Impactful Results

A recent story highlighting the importance of supporting foster families is that of the Suggs family. The Suggs family entered the foster care program as a concurrent home. On National Adoption Day in November 2015, the Suggs family finalized the adoption of four siblings who were placed in their home. LaQuaunn and Kristin Suggs knew “it was right” the first time they met Armeryone, Armonti, Rodjanae, and Semaja. They just knew: “They were our kids.” However, without the resources provided and the opportunity to meet and love these children, many families would find it daunting to take on the care of a sibling group of four.

Some “waiting children” – that is, children who have had a termination of parental rights and are available for adoption – are in foster care for just a few months, but others languish in the system for years. Concurrent foster care planning programs simultaneously prepare foster parents to support reunification with birth parents whenever possible; ensure that the children remain connected to their community, peers, and birth families; and remain open and willing to adopt if reunification does not work out. This can decrease the amount of transitions a child must go through, while increasing the likelihood of them becoming part of a safe, permanent family.

Compassionate foster parents come from many walks of life. They can be married or single, home owners or renters, employed or retired, parenting or with no children in the home. Some journey from foster care to adoption and find themselves witnesses to struggles in their communities. Whatever the prospective adoptive family’s background, a thorough homestudy process will ensure that they are sufficiently vetted before they adopt, with the goal of preparing them to meet a child’s individual needs and provide for them a permanent family.

Loushanda Battle began her journey of becoming an adoptive parent as a foster parent to a five-year-old in November of 2013. As a mother to three teenagers, Loushanda understood the bonds of siblings. When she discovered that the child she was caring for had siblings, she opened her home to the three siblings of her foster child. On National Adoption Day 2015, all of the siblings were welcomed into the family permanently through adoption, creating a family of eight. Without the support of EVOLVE’s team, Loushanda said that she might have walked away from the process. With a strong support system, she says that anyone can accept and give love to a child and help them build lasting, nurturing connections.

Steps to Expand Services

There are heavy up-front costs to effectively prepare and implement a foster care services program. Foster care agency administrative payments are only made during placement. The crucial work of setting up the privately-run program, recruiting families, licensing families, training families, and arranging placements is largely unsupported by the public sector. Private agencies are intermittently successful at securing foundation grants or community and individual financial support for their startup costs; made more difficult by the fact that funders often expect successful programming to be in place, justifying the need for funding prior to offering their support.

Every state has different laws and requirements around licensing for foster care. An agency’s initial step towards programming expansion is to communicate with their licensor. The following list includes steps EVOLVE followed when adding family services for foster youth and families in Minnesota:

- Initiate a conversation with the state licensor.

- Amend current license or apply for a new one, if needed.

- Contract for foster care administration.

- Minnesota agencies are required to have a host county contract, which can be initiated with any county willing to host the contract.

- Agencies negotiate with the host county to set agency administrative rates for supervising placement homes.

- Develop policies and procedures for the agency and families served by the program.

- Develop program forms and education training programs to include initial and ongoing training.

- Recruit families.

- License and train families.

- Once families are licensed, make county or state workers responsible for the placement of children aware of the resource families available.

- Monitor and support placements with ongoing family services and case management.

- Recruitment, licensing, and training will be ongoing processes, as you will need to continually bring in new families as licensed families adopt foster children.

Conclusion

Private agencies, particularly those with experience in international adoption, already have the expertise and many of the skills needed to recruit and prepare families and support them through the adoption process. They can help kids in their own communities by focusing on proactive community engagement, effective case management, and delivery of proven family post-placement support services. Private agencies can be just as successful in helping to create positive outcomes for local youth as public agencies. Public/private partnerships can ensure that children receive the benefits and strengths of both programs. Collaboration between agencies and other community stakeholders positively impacts permanency outcomes for children being served by the foster care system.

Private agencies can also play an important role in advocating for policy changes supporting efforts to secure permanent, loving homes for children in the foster care system when reunification is not possible. We know that the safety, security, and bonds between a child and a caring adult are essential to healthy development, which in turn contributes to healthy and productive communities. Child-focused advocates must continue to engage legislators and state agencies to examine and advocate for laws, policies, and funding that will most effectively serve children in their communities and allow public and private agencies to work together in the best interests of children. Youth in foster care deserve the very best efforts of all those in their community equipped to help them find permanency.

References

- “How Many Children Were Adopted in 2007 and 2008?” Children’s Bureau and Child Welfare Information Gateway, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Retrieved online at: https://www.childwelfare.gov/pubPDFs/adopted0708.pdf

- Children’s Bureau, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. The AFCARS Report. Retrieved online at: http://www.acf.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/cb/afcarsreport22.pdf

- Courtney, Mark E., et al. Midwest Evaluation of the Adult Functioning of Former Foster Youth: Outcomes at Age 26. 2011: Chapin Hall at the University of Chicago. Retrieved online at: http://www.chapinhall.org/sites/default/files/Midwest%20Evaluation_Report_4_10_12.pdf

- Jim Casey Youth Opportunities Initiative. Aging Out. Retrieved online at: http://www.jimcaseyyouth.org/about/aging-out

- Zill, Nicholas. “Better Prospects, Lower Cost: The Case for increasing Foster Care Adoption.” Adoption Advocate No. 35. May 2011: National Council For Adoption. Retrieved online at: https://adoptioncouncil.org//images/stories/NCFA_ADOPTION_ADVOCATE_NO35.pdf

- Sharp, Wayne. “The Human, Social, and Economic Cost of Aging Out of Foster Care.” Adoption Advocate No. 83. May 2015: National Council For Adoption. Retrieved online at: https://adoptioncouncil.org//publications/2015/05/adoption-advocate-no-83

- Learn more about child focused recruitment: Dave Thomas Foundation for Adoption: Wendy’s Wonderful Kids. Retrieved online at: https://davethomasfoundation.org/learn/research/

- For more on trauma-informed care: ChildTrauma Library. Child Trauma Academy. Retrieved online at: http://childtrauma.org/cta-library/

- For more in independent living: Child Welfare Information Gateway. Transition to Adulthood and Independent Living. Retrieved online at: https://www.childwelfare.gov/topics/outofhome/independent/